The energy and life force of water is at the centre of the ‘23rd Biennale of Sydney: rīvus’.

Drawing context from the Latin word rīvus meaning stream, this year’s biennale takes a deep and revealing dive into the relevance, history and future of water ecology and our relationships with the natural world, both connected and disconnected. It has been curated by Artistic Director and Colombian curator José Roca with co-curators Paschal Daantos Berry, Anna Davis, Hannah Donnelly and Talia Linz.

Until 13 June, more than 330 new and commissioned works including large-scale immersive installations, site specific projects, and living works by over 80 national and international participants punctuate rīvus aside the waterways of the Gadigal, Barramatagal and Cabrogal peoples.

Audiences are invited to explore the diverse range of exhibits at the Art Gallery of New South Wales (AGNSW), Museum of Contemporary Art Australia (MCA), and the National Art School (NAS) working in partnership with Artspace and Pier 2/3 at Walsh Bay Arts Precinct, and at the Arts and Cultural Exchange in Burramatta/Parramatta.

An expansive program of events and experiences titled The Waterhouse, including back to school programs are anchored around Barangaroo and The Cutaway, including walks, talks, workshops, and activities, as well as Art After Dark on Wednesdays, from 5-9pm.

With the inclusion of bodies of water and their custodians such as Australia, Bangladesh and Ecuador, as rīvus participants, the curators explain that “Rivers have been the ways of communication and the givers of life for entire communities and a growing number of jurisdictions around the world are granting rivers legal personhood rights.”

The concept of environmental personhood recognises the legal rights of nature and takes into consideration Indigenous knowledge of caring for the environment. It accepts living entities such as wetlands, oceans, forests and other ecosystems – not as property but as natural systems that have a right to exist without devastation.

Ecuador was the first country to implement the Rights of Nature in its Constitution in 2008. Bolivia, New Zealand and India are among others to have joined the cause, and in 2017 Australia passed the Yarra River Protection (Wilip-gin Birraraung murron) Act 2017.

“As we see waterways having a voice in the courtroom, we wanted to extend this further into the public sphere with our exhibition. Many of the Biennale of Sydney participants have worked with waterways, local and international, to share their stories and raise these important conversations,” the curators add.

What to see at the Biennale of Sydney

My first port of call was the MCA. To name just a few of the impactful works on display, on level 1, in the Voice of the Birrarung, 2022, Uncle Dave Wandin, Wurundjeri Elder and Knowledge Holder from the Yarra River region in Victoria addresses viewers about the importance of caring for the Yarra River and the role he plays in it. Also in this space, a series of Ink-jet and watercolour prints by Brazilian artist Caio Reisewitz leads viewers to a large-scale collage entitled MUNDUS SUBTERRANEUS, 2022, which brings focus to the destruction of the natural world slated by capitalism with particular reference to the aquifer that runs under the Amazon.

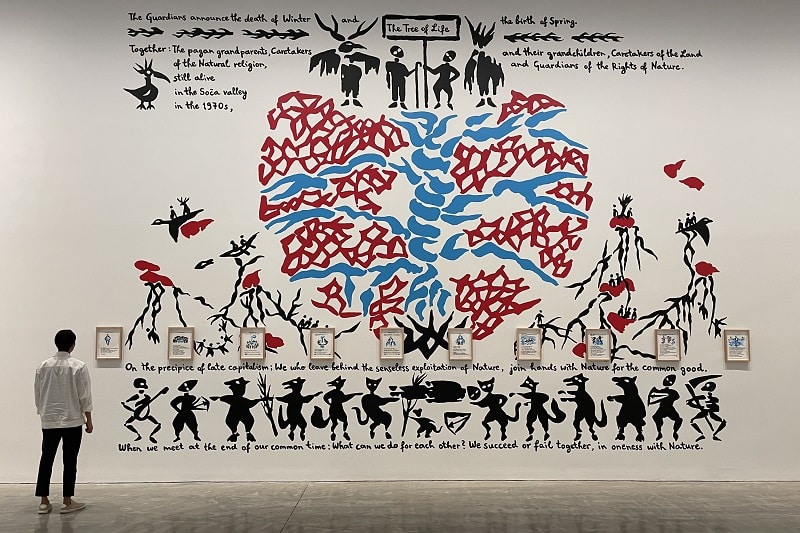

A collaborative wall drawing created by Slovenian artist Martjetica Potrč and Wiradjuri man and artist Uncle Ray Woods overwhelms the space across two monumental works The Time of Humans on the Soča River, 2021 and The Time on The Lachlan River, 2022. Painted directly onto the gallery walls these works tell the tale of two rivers, thousands of kilometres apart, but sharing the same struggle – to protect the rivers from the powers of privatisation and commercialisation. These are presented alongside Potrč’s installation The House of Agreement Between Humans and the Earth, 2022, a log structure looking at the relationship between humans and the natural world.

Upstairs on level 3, two surreal landscape paintings by Brazilian artist Alec Cerveny represent an eery depiction of the real world alongside a dystopian territory drawing attention to the ongoing impact of Dutch, Spanish and Portuguese colonisation on South America’s Indigenous people and their culture.

Using the mechanics of a palimpsest machine (a modified 3D printer) Brisbane-based artist Robert Andrew presents an evolving wall work. The machine moves around the wall as canvas stopping at intervals to spurt trickles of water onto the surface that over time is washing away layers of earth pigment and chalk to reveal ‘lines of text in Yawuru language that bleed through the white surface, creating ochre-stained tributaries’ to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and language lost through colonisation.

Five large and intricately mastered tapestries by New-York-based German artist Kiki Smith draw on the visual and storytelling cues of folklore, fairytales, mythology, feminism and religious iconography, to express themes of climate change and climate justice, connecting us with animals and the natural world from the forest floor to the starlit skies. German artist Julia Lohman presents a marine-based installation titled Corpus Maris I 2022, a sea-snail-like creature made of seaweed, rattan and plywood, protruding into the gallery space as if making its own enquiry of the passers-by.

Venezuelan artist Milton Becerra presents a marvellous installation of three large stones held suspended in space by a calculated network of fine and colourful threads, which form the structural elements that hold the stones. Based on geometric abstraction, grids and optical illusion Lost Paradise – Vibrational Energy H20, Sydney 2022, echoes the energy that emanates from the natural world.

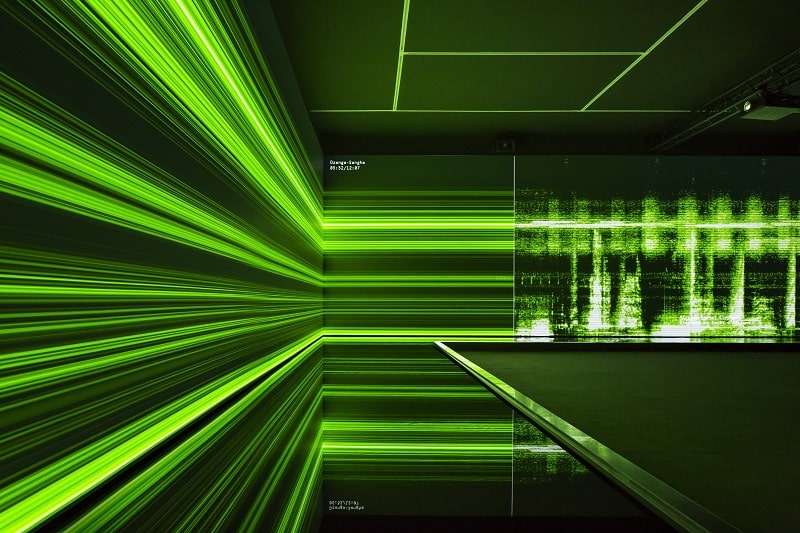

A short walk from The Rocks to Stargazer Lawn and audiences are invited to be immersed in the light-based visual effects and alluring sound work of The Great Animal Orchestra, a major installation created by American soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause with United Visual Artists. The meditative environment envelops the audience in a choir of song from over 15,000 birds, insects, whales, and other animals calling out across some of the most vulnerable natural habitats in Africa, North America, the Pacific Ocean, and the Amazon River.

This is a space for deep listening, and a time to reflect on caring for non-human life. The most confronting discovery of this work is the realisation that over a period of 50 years a devastating silence caused by human activity in the natural world has fallen over what were once richly inhabited natural environments.

Visit the ‘Biennale of Sydney: rīvus’ website for more information about participating artists, exhibitions and venues, and the entire program of free events.