‘Don’t Shoot the Messenger’ by Luke Cornish features 54 unique hand cut stencil works created over the course of 2020 which protest and spotlight injustice. The artist, also known as ELK, opens his show this week at aMBUSH Gallery Kambri in Canberra on 12 March.

Recently the artist parted ways with two commercial galleries representing his work and he’s now making art on his own terms which includes the subversion of religious iconography, weapons and using international currency. This is where the exhibition’s title emerges. If you find the imagery shocking or violent maybe that’s because it is – ‘Don’t Shoot the Messenger’. Created after Cornish’s plans for overseas travel were off the table, the new artworks still include photos from past journeys in countries including Syria, China, the USA, Afghanistan and the Philippines.

We had the pleasure of speaking to the artist ahead of the exhibition’s opening night.

Do you remember when you first felt ‘this is wrong’ and that you could say something about it with your art?

I remember the moment precisely actually, I was driving down Captain Cook Crescent in Griffith, Canberra on the 20th of March 2003, it was around 4pm, and I was listening to the radio coverage of the imminent American invasion of Iraq. The feeling ‘this is wrong’ is an understatement, I remember feeling so angry and frustrated at the injustice of this illegal war. This was also the precise moment that triggered an explosion of street art on the streets of Melbourne, if not the whole planet.

How do you navigate presenting confronting imagery while trying to engage empathy with difficult subjects?

To be honest, I don’t really overthink it. The work is coming from a place of integrity, but I do sometimes miss the mark and inadvertently offend people that I had no intention of upsetting. I’m always willing to listen and take on board opinions on sensitive subjects that people hold close.

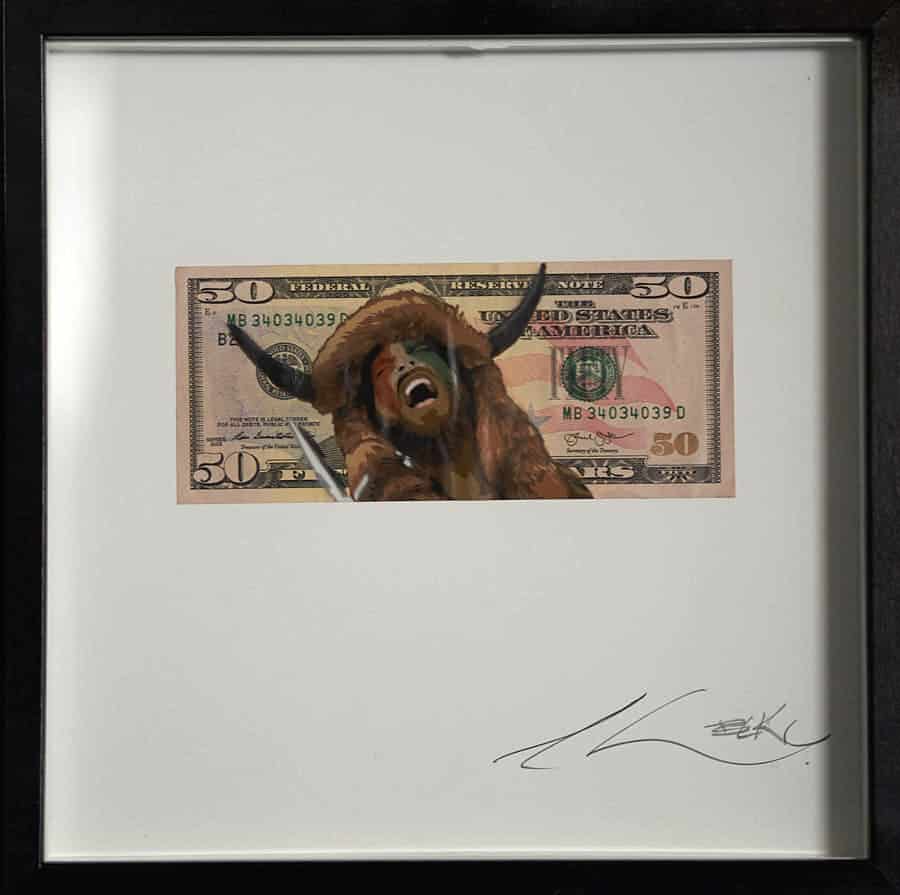

The banknotes I have been collecting from my travels over the last few years (though the more obscure ones come from eBay) and the images I chose for the notes depicts the atrocities and absurdities the individual countries face, whether its the African slave trade in Libya, Homosexual men being executed in Iran or the storming of the US Capitol building. Some of them are funny too, a spoon full of sugar to make the medicine go down.

Your imagery is very direct, one immediately senses protest and that you’re calling out injustice. Do you see art as an answer or a provocation?

Art is not the answer, it is the question. These problems are too big for any one person to solve alone, and unfortunately they’re only ever in the public conscious for as long as Rupert Murdoch wants them to be. It’s important to keep these important issues front and centre, to expose and educate people to what’s happening in the world, hopefully people will absorb and disseminate this information, that’s where change comes from, people.

What is being said here that you felt unable to share before under commercial representation?

The commercial art world is a little risk averse, I understand, they have overheads, and exhibiting a painting of a guy getting his head cut off is always going to be a hard sell. As an artist I need the freedom to make the art that I want to make, regardless of how violent or offensive it may be.

The work needs to be authentic and I need freedom to fail and make mistakes, you don’t get much of that in galleries.

The dynamic between oppressed people and the abuse of power is very prevalent in your work, can you talk about why it’s important to visualise this?

Journalism is dead in this country. It’s the artists that now hold truth to power.

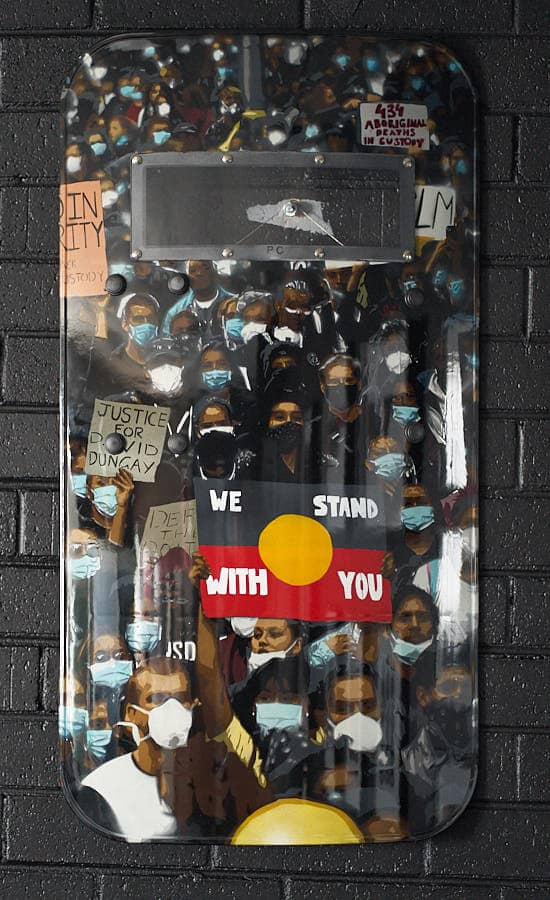

The imagery on the riot shields is like a mirror to society. Why is it important that these images proliferate?

I did want these image to be a reflection, an actual reflection of what the person holding the shield might see. I like to think it’s helping to raise awareness to the issues they are depicting.

You’ve worked with stencilling as a street artist and also on 2D formats for gallery shows. What’s it like applying this method to objects technically and how does it feel conceptually?

My work has been predominantly stencil art since day one. Hand cutting stencils is an almost meditative process, it’s all about getting into a flow state and forgetting about the clock ticking. My attention span is non-existent in mostly every other facet of life, but I’ve found with stencils, I always been able to cut away for hours without losing patience. Perhaps it’s just a medium I can pour my OCD into.

There is some dark humour woven into the show with that iconic image from ‘The Shining’ as a nod to the emotional impact of home-isolation. How do you keep balance and joy in your life more generally when engaging with the subjects you do?

I have a pretty dark sense of humour; it’s an important part of staying sane while exposing myself to the horrors of this planet over coffee every morning. I also have a fat little bulldog that needs to be walked, albeit briefly, a couple of times a day, which gets me out of my studio bubble. Fresh air and regular exercise are the key to staying balanced as a full time creative, the rest sorts itself out.

What do you hope to communicate through images of violence on weapons?

The idea behind this work, which I began creating at the very start of covid, a time when people were literally fighting over toilet paper, a time that felt like the end of the world, is basically a barometer for the exact point of societal collapse, that the weapon becomes more valuable, than the artwork on it.

The exhibition will be open free of charge to the public until Sunday 11 April (showing daily from 10am-6pm weekdays and 12pm-5pm on weekends). All works are for sale and attendance is free of charge.