Throughout history, there has been much intermixing between the Japanese archipelago and the Korean peninsula – benign and otherwise. Today, the relationship between the two countries is darkened by Japan’s imperial history with Korea, and its consequences – nowhere better exemplified than in the plight of the Zainichi.

Japan occupied the Korean peninsula for 35 years. During WWII, the Japanese Empire turned Korea into its factory, and conscripted thousands of Koreans into forced labour and sex work. By the end of the war – and Japan’s colonisation of Korea – over 2 million Koreans were living in Japan.

While many returned to Korea as soon as they had the chance, hundreds of thousands remained. Today this population remains stable at about 600,000 ethnic Koreans – known in Japan as ‘Zainichi’.

Zainichi – a Racist and Complicated History

During the colonial years, Japanese imperial policy painted Koreans as inferior, while simultaneously seeking to assimilate them. The Empire promoted mixed marriage, and banned the teaching and use of Korean language, urging all citizens to see themselves as Japanese subjects.

After colonial rule ended, ethnic Koreans living in Japan lost their rights, but not their oppression. In 1945, Zainichi Koreans lost their right to vote, and most were kicked out of government jobs for no longer being ‘Japanese’.

Simultaneously, Zainichi were denied the right to establish ethnic schools because they were ‘Japanese nationals’. Some were even arrested as Japanese war criminals. Socially, Zainichi continued to face animosity and discrimination from ethnic Japanese – despite the fact that by 1951, 63% of Zainichi were born in Japan, and 43% couldn’t speak Korean.

As Professor John Lie writes for the Association of Asian Studies, “Government policy came close to apartheid or Jim Crow laws”. The Japanese welfare state ignored Koreans, and banks often refused to lend to Korean businesses.

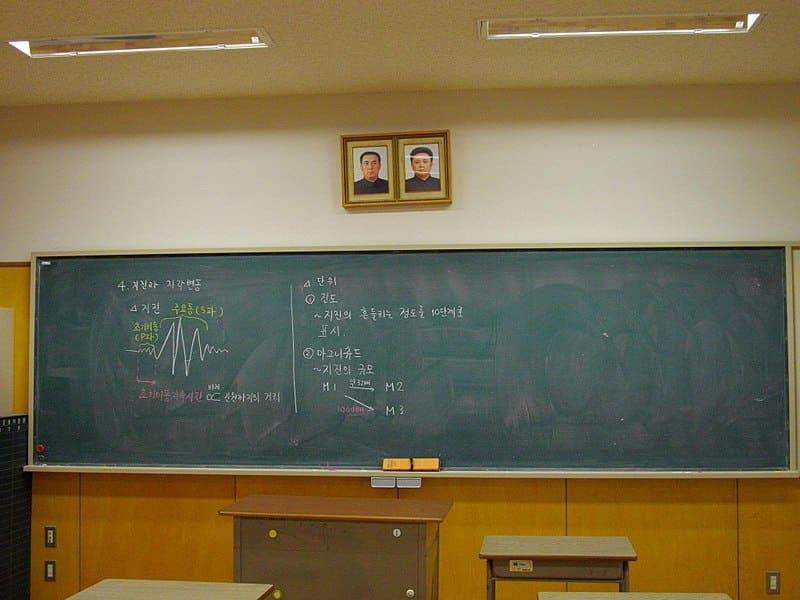

So in the 1950s, an organisation called Sōren (also known as Chongryon) stepped in to fill the gap.

Sōren provided loans for Zainichi businesses, and established schools for Korean communities, with an eye to prepare pupils for eventual return to the homeland. In the late 50s, Sōren ran a repatriation project, encouraging Zainichi to return to North Korea.

But the poverty-stricken and autocratic reality of the Kim regime led to the failure of the project just a few years after its birth. Estrangement from the North-affiliated Sōren grew with the Japan-South Korea Normalisation Treaty of 1965, which implied reunification was a pipe dream.

Still, Zainichi did not turn to South Korea and its associations in Japan. In the 1970s, South Korea was a military dictatorship, and ethnic Koreans in the modern democracy of Japan were alienated from the South as well as the North. The Zainichi identity was a lonely one, characterised, as Lie writes, by “fundamental illegitimacy—disrecognition”.

Today’s Reality

These days, animosity towards Zainichi is far less universal, but also far from eradicated.

Discrimination – while outlawed in the constitution – is not illegal, and the government only passed a hate speech law in 2016 (with no consequences for perpetrators).

The Japanese government has still not explicitly apologised for its forced sex trafficking of Korean women (referred to as ‘comfort women’), and regularly engages in revisionist behaviour when it comes to its historical abuses.

Japanese hatred of Koreans, simmering quietly most of the time, rises to the surface in moments like former-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination. After he was fatally shot on July 8th, the internet was flooded with posts spewing anti-Korean hate and claiming the shooter must have been Zainichi, or working for the CCP.

Just last year, a young Japanese man pleaded guilty to arson after torching several houses in Utoro. The culprit confessed he was trying to “intimidate and force out” Korean residents.

Extremist groups like Zaitokukai continue to spout their right-wing nationalist agenda, calling Koreans “cockroaches” and urging them to “go home” or die. Hate speech and racist abuse peaks every time Pyongyang launches a missile too close to the Japanese archipelago.

Abe himself served as “supreme adviser” to Nippon Kaigi, an ultranationalist, revisionist organization that defends the country’s “imperial glory”.

While social and governmental standards are slowly becoming more progressive, with incidents of anti-Korean violence dwindling, global trends towards extremism and populism should not be ignored. The Internet provides a largely-unregulated arena for racist agendas. Given Japan’s abusive history, it needs to take more decisive steps in the present.

Cover photo: “File:Demonstration by zaitokukai in Tokyo 2.jpg” by Kurashita Yuki is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Follow Maddie’s journalism on Twitter.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter