Even according to the lowest estimates, hundreds of thousands of Aussies currently have Long COVID, or will soon develop it. But the disorder itself is notoriously elusive – wickedly hard to classify, and with no definitive treatment.

Kimberly Knackstedt, former director of disability policy for the Biden administration’s White House Domestic Policy Council, says “The one thing I’m hearing more than almost anything else is, ‘My doctor doesn’t believe me’”. Part of the reason for this is the lack of consensus on defining Long COVID, or on best practices to treat it.

There aren’t really any pathology tests widely available to diagnose Long COVID. Patients may be suffering from debilitating fatigue, headaches, chest pain and more, and yet return healthy pathology results. One physiologist, Etheresia Pretorius of South Africa’s Stellenbosch Uni, has a theory as to why.

Pretorius’ research suggests traditional lab tests might not pick up inflammatory molecules because they’re trapped in ‘microclots’. Pretorius, along with her long-time colleague Douglas Kell (University of Liverpool), are the leading proponents of a theory that says microclots are to blame for Long COVID symptoms.

Microclots – what are they?

When we suffer injury or illness, our bodies can sometimes react by creating small clots in the bloodstream. Usually, these clots will then be dissolved through a process called fibrinolysis.

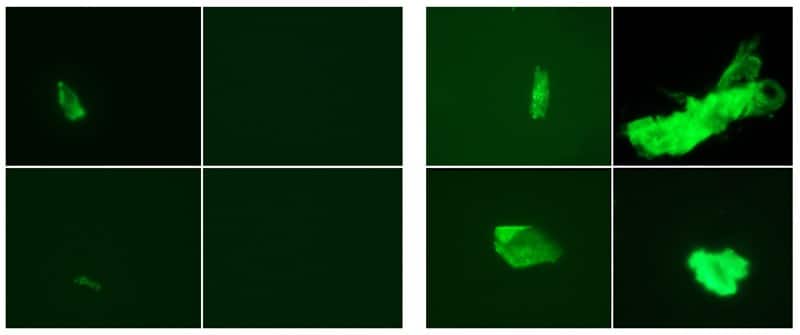

But Pretorius’ experiments suggest that in Long COVID patients, the body creates microclots that are resistant to fibrinolytic processes. These microclots, which have been observed by their team in other conditions like diabetes and Alzheimer’s, look “horrible, gunky, dark,” says Kell.

Pretorius, Kell, and their team are the only group that has published results on Long COVID-associated microclots. They’ve done so in several studies, but other, larger COVID studies have failed to yield similar evidence.

Still, their results have been replicated in an unpublished study out of the UK, and their hypothesis aligns with other clotting data. People with COVID-19, especially in severe cases, are undoubtedly more likely to develop clotting, as the virus affects the vascular system, damaging blood vessels and triggering clotting. Several studies have suggested that for some, clotting tendencies brought on by COVID persist months after initial infection.

But other experts are more sceptical about Pretorius and Kell’s theory. “I’d like to see confirmation from other investigators,” says haematologist and clotting expert Jeffrey Weitz. Weitz criticised the method Pretorius and Kell used to identify microclots, saying it “isn’t a standard technique at all”. Others say it isn’t clear if abnormal microclots are actually causal for Long COVID, or just another phenomenon associated with COVID.

Pretorius thinks studies proving Long COVID sufferers improve after receiving anticoagulation therapies would be definitive – the preprint of a recent study of hers contains evidence of this.

The microclot theory is one of the more popular ones among Long COVID sufferers, and has led to many traveling to specialist clinics to receive blood filtering procedures and anticoagulant medication.

“It’s a completely rational response to a situation like this,” says Shamil Haroon, a researcher on Long COVID treatment. “But people could potentially go bankrupt accessing these treatments, for which there is limited to no evidence of effectiveness.”

Australia’s House Health Committee has announced it will launch an inquiry into Long COVID, its impacts and treatment.

Cover photo by ANIRUDH on Unsplash.

Follow Maddie’s journalism on Twitter.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter