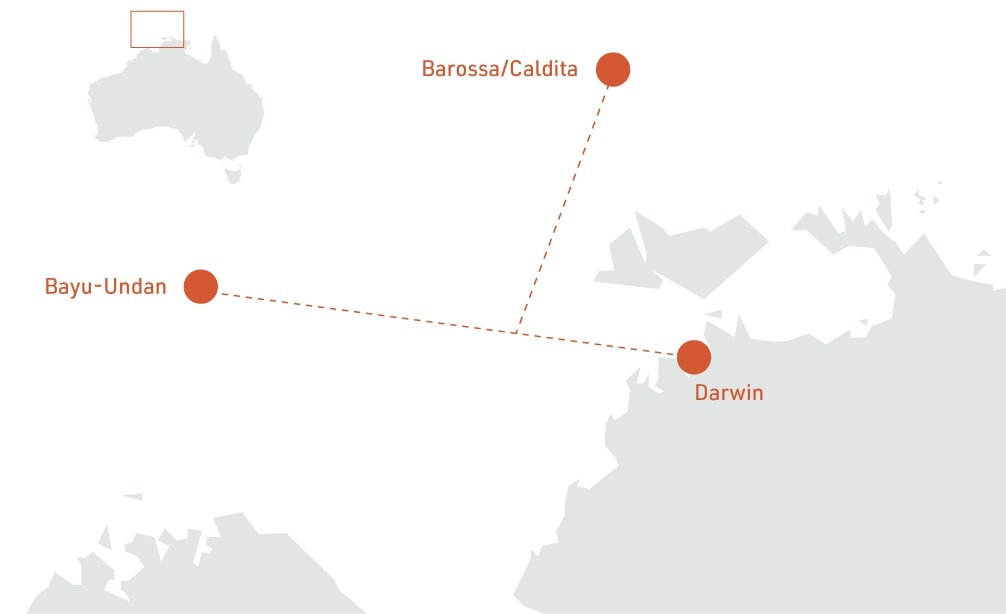

On 21 September, Santos lost a Full Federal Court appeal against a judicial review ruling that it failed to consult with a Tiwi Islands elder over its off-shore Barossa Gas Project. The court’s full reasons were published earlier this month.

The Federal Court decision marks a dramatic about-face for the Barossa project. Santos’ “Environmental Plan” (EP) was initially approved by the regulator in March.

But in August, on a single-judge Federal Court judicial review brought by Dennis Tipakalippa, an elder of one of the Tiwi Islands’ eight clans, that approval was overturned. The oil and gas development regulations require all persons with “relevant interests” to be consulted, and Mr Tipakalippa wasn’t. Santos then disputed the judicial review’s decision before the full-bench of the Federal Court.

The case was novel because in Aboriginal land rights law, indigenous land rights end at the sea. Tipakalippa argued that his clan’s “sea country” constitutes a “relevant interest” in the terms of gas development regulations, which obliged Santos to consult with them.

As the court put it, “Their asserted rights to that sea country are based upon longstanding spiritual connections as well as traditional hunting and gathering activities in which they and their ancestors have engaged.” Tipakalippa has said the development would damage fishing and block the migratory path of a native sea turtle.

In a classic barrister move, Santos’s lawyers argued there is nothing in the environmental regulations mandating them to consider “sea country” but, if the judges decided that there is, then the judicial review judge shouldn’t have inferred that they didn’t!

Santos also claimed it was “unworkable” to consult every relevant person, to which the Federal Court responded wrly: “Granted, a consultation with First Nations groups may not be as simple (or quick) as sending an email with a package of information, which is apparently how Santos demonstrated it had consulted the TLC [Tiwi Land Council]. Since the TLC did not, in this proceeding or otherwise, complain that such conduct was insufficient or inadequate consultation under reg 11A, we say no more about it.”

This, by the way, is the “consultation” Santos trumpeted in its statement following the Federal Court decision. The statement was pure PR, as in the case itself Santos’ lawyers said “Santos does not rely on an argument that consultation with the Tiwi Land Council (TLC) discharged an obligation to consult with the traditional owners.”

Of course, activists have been mobilising on other grounds than sea country rights. Opponents say the Barossa project would be responsible for 15.6 million tons of carbon dioxide emissions every year. Feeling the heat, Santos recently withdrew its sponsorship of the Darwin Festival.

At current prices, the Barossa gas is worth approximately $16.5 billion. Judging by Santos’ previous record, this would mean $2.8 million in tax revenue for Australia.

So the Barossa project is stalled for now. The legislation doesn’t say, however, what follows once Santos proceeds to carry out proper “consultation”. What if the indigenous organisations consulted never approve of the project?

As it stands, the legal framework doesn’t allow indigenous owners the right of veto over such projects. But as small consolation perhaps, these processes at least allow traditional owners – or the bodies representing them – to jockey for a greater share of the economic benefits from such projects.

Follow Christian on Twitter for more news updates.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter