I think it’s fair to say that Mothers are mostly visible in art history inhabiting the role of parent, the Madonna and Child is a good example of this. Also, the idea of fertility is often summoned in painting and art objects, think of the Venus figures such as ‘The Venus of Willendorf’ (Jeff Koons did an ode to the Venus form in hot pink steel.) But what about the storytelling of the space in-between, a woman’s transformation during pregnancy?

The sporting body, the dying body, and the sexual body are readily represented in art but I wonder if the pregnant body is as ubiquitous. My guess is, no. The following ruminations are intended to collate ‘the art of pregnancy’ and are an incomplete list to which I welcome additions.

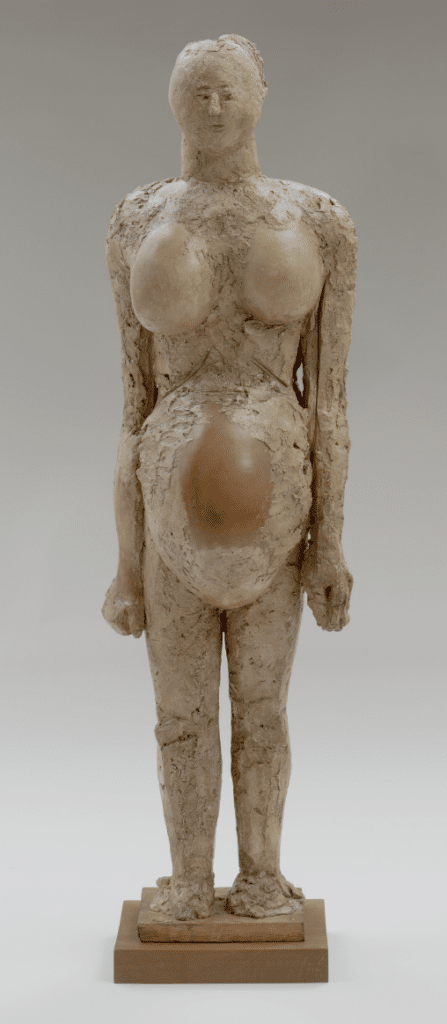

Australian artist Ron Mueck acknowledged he created the sculpture ‘Pregnant woman’ 2002 in response to representations of mother and child on view at the National Gallery, London. Mueck worked with the model between 6 and 9 months of her pregnancy. The artist created the form to be larger than life at 2.5m tall, we look up to her, see her presence and perhaps note her experience as monumental. And yet, as the National Gallery of Victoria have noted ‘She is exhausted, hands held back over her head; the face is tender and vulnerable. Her presence is powerful, evoking a multitude of thoughts, ranging from the wonder of maternity and procreation to population control and the burden of female responsibility.’ Her closed eyes facilitate our gaze and also are a cue to an inner journey and focus taking place.

In 2023 it seems popular in commercial and fashion photography (Demi Moore, Serena Williams, Rihanna to name a few) as well as on social media for women to share images of their changed bodies in this liminal and incredible period of life, inspired by the desire to share their story (a driving force in art generally?) So if the subject is part of pop culture is its place in art history minor because the authors of the image of the pregnant body are largely women, is the pregnant body considered private, or is its representation tied to anxiety or superstition? Further, which bodies are elevated to ‘high art’, does diversity in this category exist?

Before we enjoy contemporary representations let’s turn to the past. Some notable representations of pregnant bodies include the Arnolfini portrait by Jan Van Eyck, 1434, Raphael’s La Donna Gravida and Gustav Klimt’s, Hope, II 1907-08.

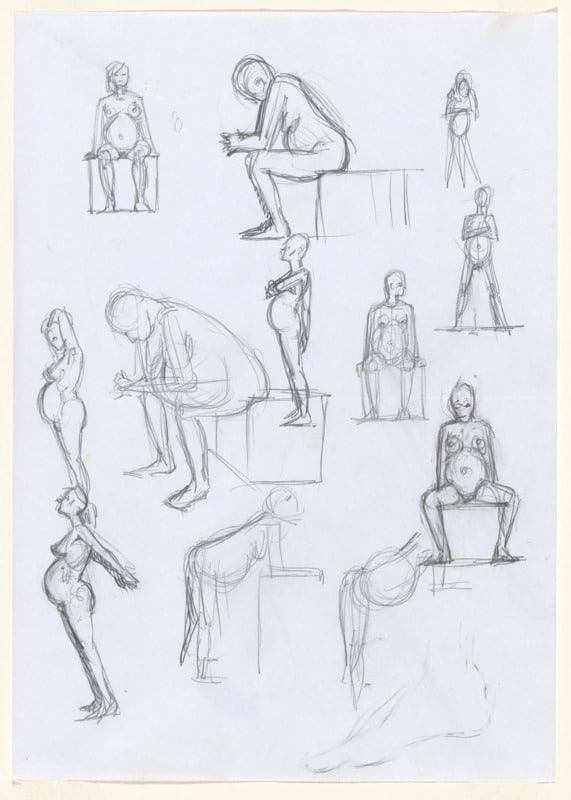

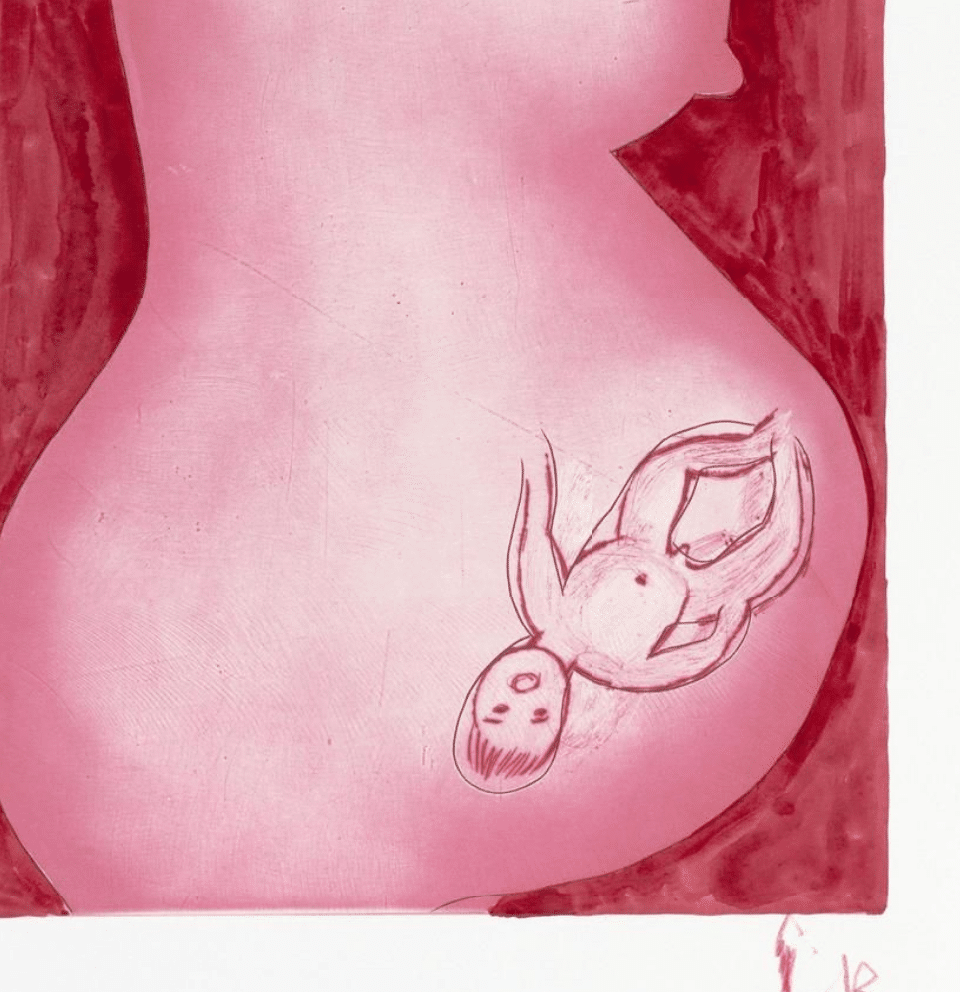

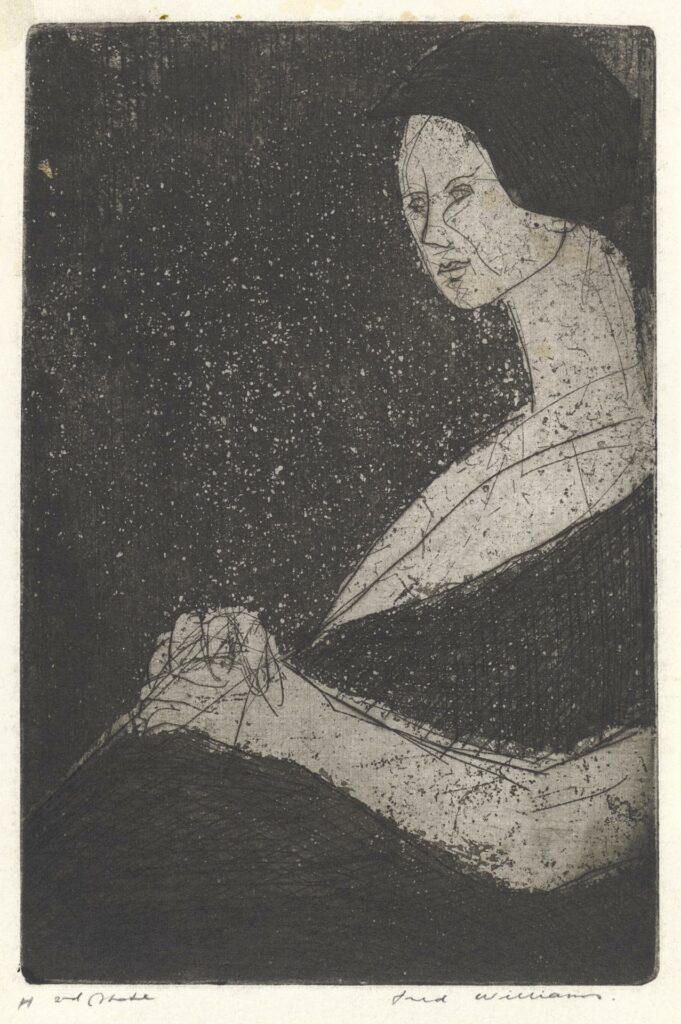

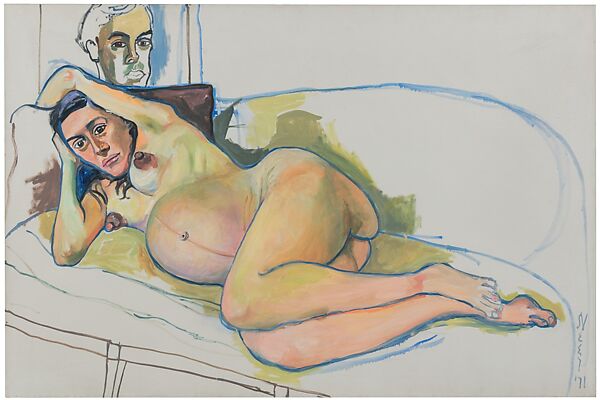

Some time later we have Pablo Picasso’s Pregnant Woman Vallauris, 1950, Louise Bourgeois created many works inspired by the pregnant form such as the print series Pregnant Woman, 2008, Fred Williams’ Pregnant Woman 1955-56, Alice Neel painted Pregnant Woman in 1971 and Lucian Freud painted Pregnant Girl 1960-61.

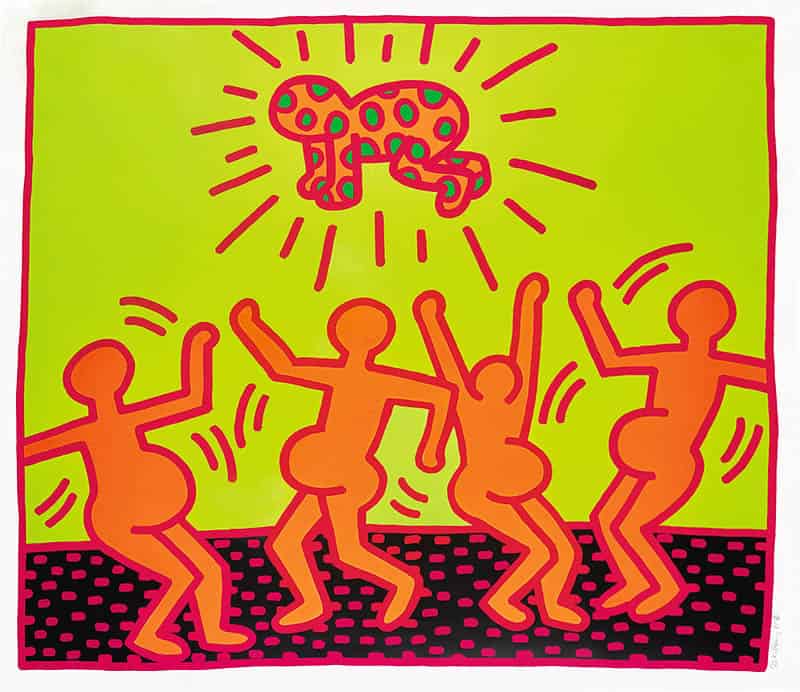

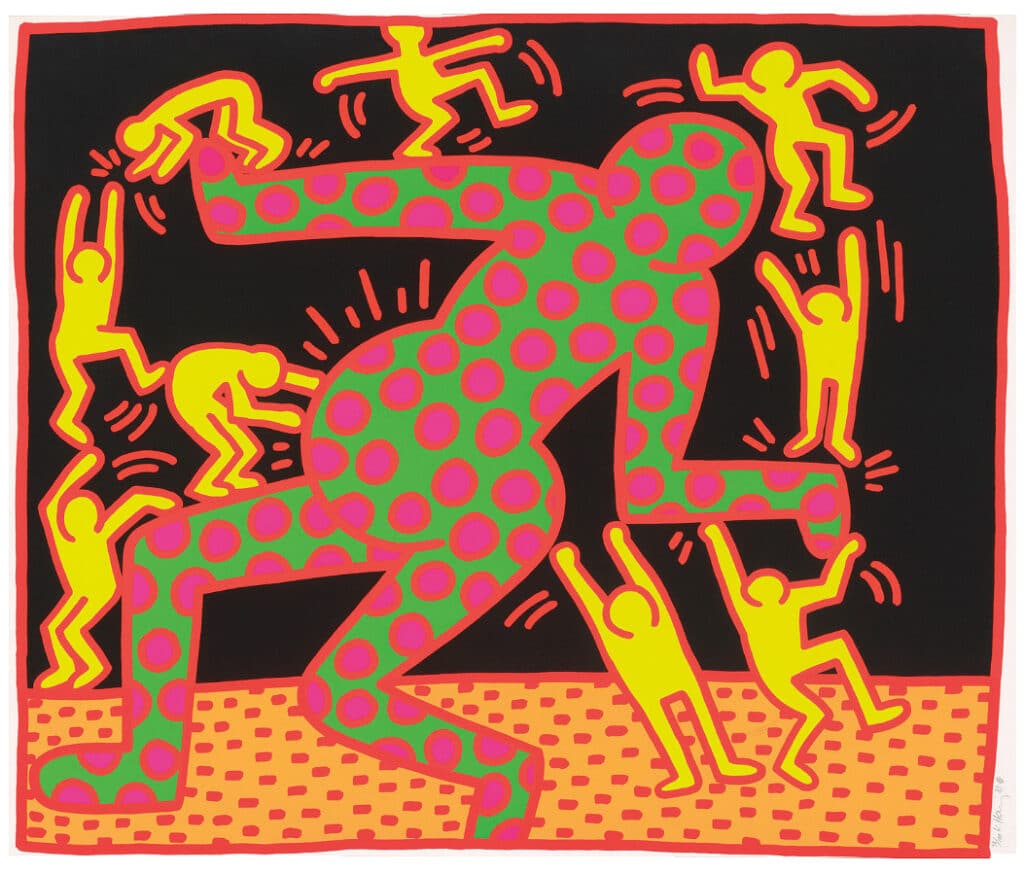

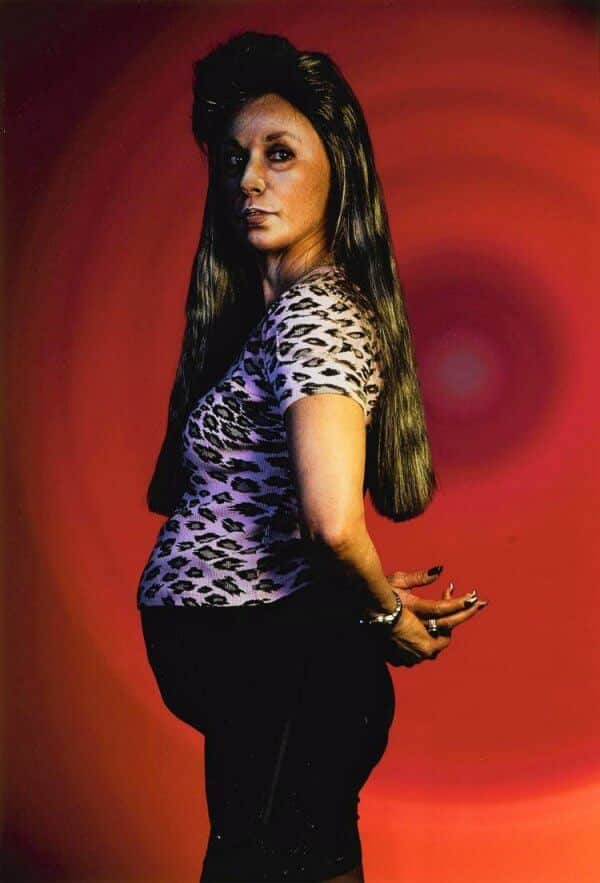

In the 1980s Keith Haring created a series of works about fertility which depicted the pregnant form, collectively titled the ‘Fertility Suite’. Fellow US artist Cindy Sherman made works about ten years apart that show the artist, as is her signature, depicting herself as a pregnant character.

Entering the noughties, Marc Quinn created Alison Lapper (8 months) in 2000. On the work and subject he said ‘Marble is the material used to commemorate heroes, and these people seem to me to be a new kind of hero – people who instead of conquering the outside world have conquered their own inner world and gone on to live fulfilled lives. To me, they celebrate the diversity of humanity. Most monuments are commemorating past events; because Alison is pregnant it’s a sculpture about the future possibilities of humanity.’

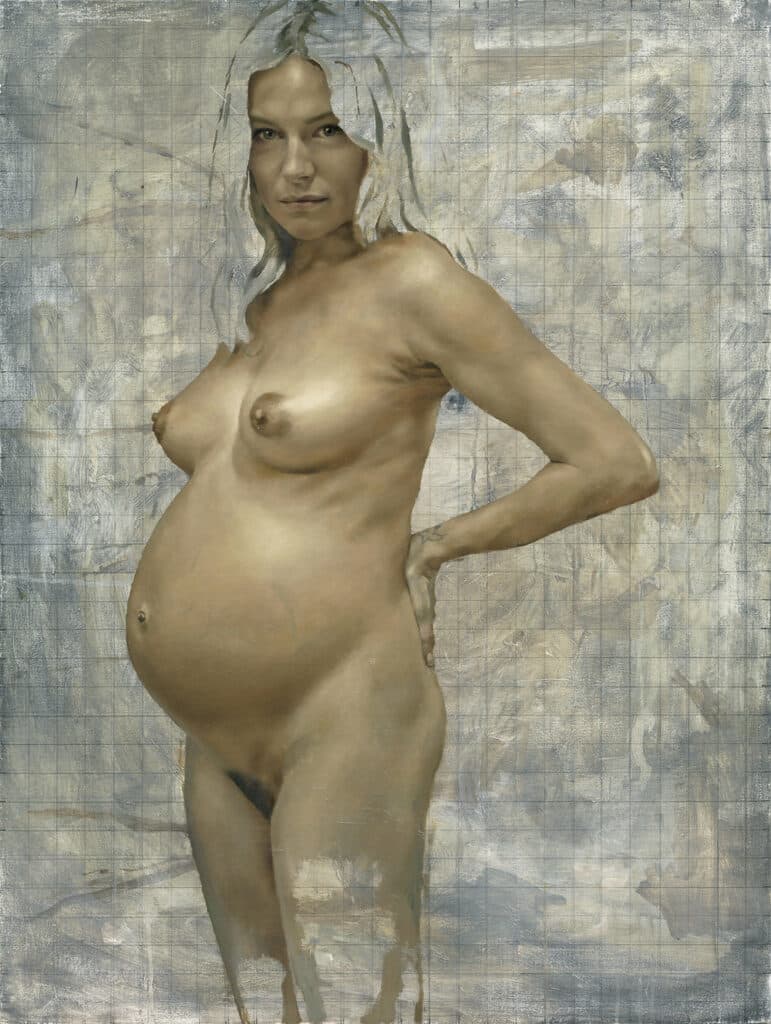

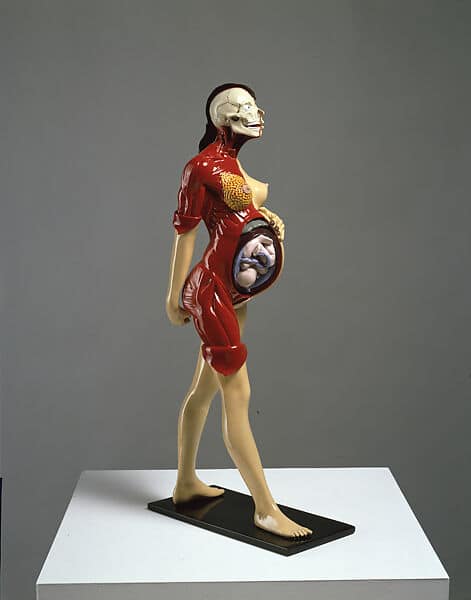

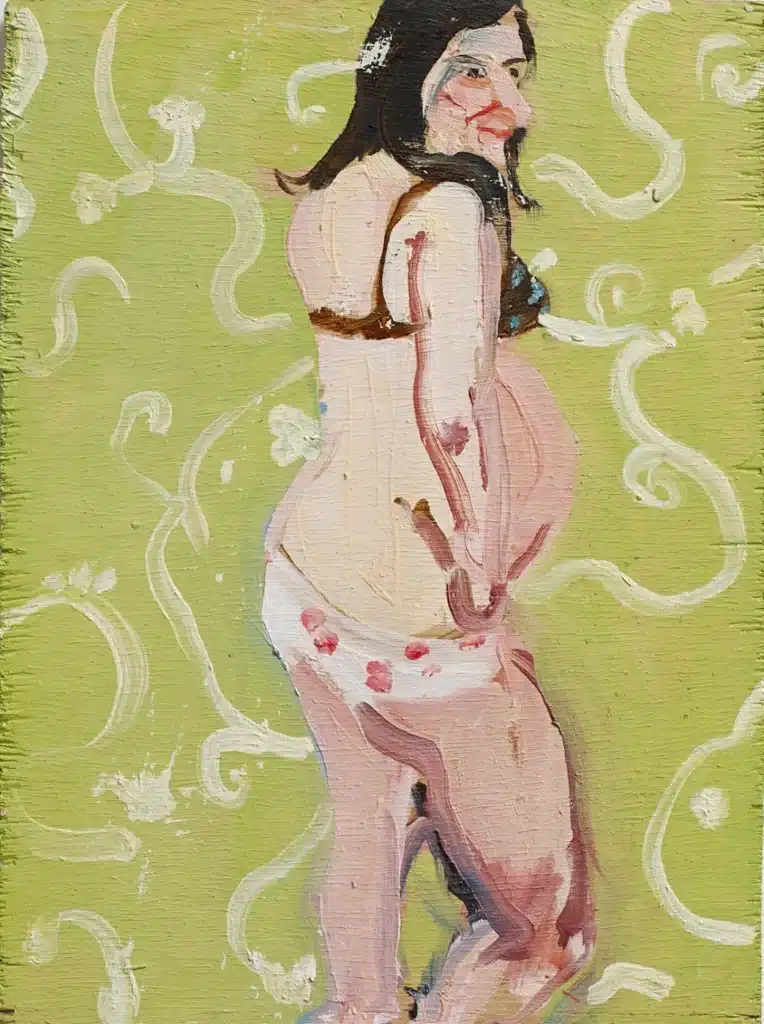

The contemporary art canon of pregnant bodies includes Chantal Joffe’s paintings, Damien Hirst’s interestingly titled Virgin (exposed) and Jonathan Yeo’s portrait of Sienna Miller.

In recent memory artist Natasha Bieniek shared Waiting for Arden, in the 2019 Archibald Prize at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney. She commented; ‘I felt compelled to use myself as a subject because I was completely consumed within my own world. It reflects a moment in time when I was feeling particularly uncomfortable and apprehensive about what I was about to face. Although I already felt immense love for my baby, I had anxieties about becoming a mother and how my ability to make art would be called into question. Painting was my life. I wondered how my integrity as an artist might be scrutinised. I feared that my painting would not be looked at beyond the scope of motherhood.’

That same year, and prize Katherine Edney shared Self-portrait with Ariel. She noted ‘I had been documenting my body’s changes throughout my pregnancy, as I was in awe of the strength of the female body and its extraordinary capabilities. I wanted to capture this physical and psychological transformation, while also revealing my vulnerability. I have always battled migraines and anxiety and for the first time I had never felt better. It was my desire to portray this ethereal state of tranquillity and overwhelming sense of calm and wellness. I chose to capture this private moment on a relatively small scale, so that the work could remain intimate for the viewer.’

Sophie Penkethman-Young presented her pregnant body in the performance piece ‘Birth Plan’ at Carriageworks, Sydney stating ‘What better time than this to present my birth plan to my sector peers and the general public. Like any strategic document, the birth plan has been developed through a process of community consultation, research and assessment.’ Similarly, American artist Marni Kotak used her pregnant body as the medium in performance work The Birth of Baby X, 2011. Kotak recorded her thoughts and feelings in the lead up to the birth, as well as permitted the labour itself to become part of the artwork.

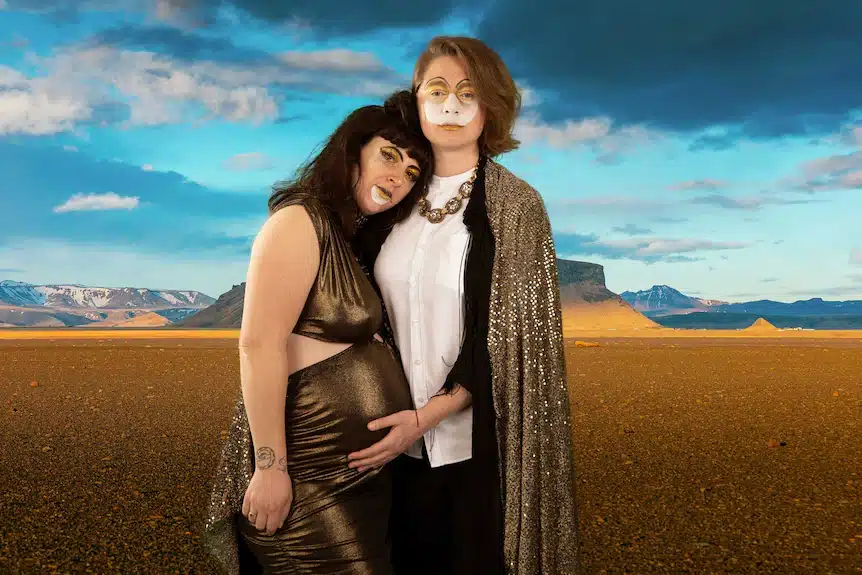

Australian artist Casey Jenkins has created several works which address conception and having a child, and with specific reference to the pregnant body she shares ‘Maternal Distress’ and ‘Growing Change’. In contemporary portraiture at home, Hannah Bronte shared Still I Rise and EO Gill created a series of portraits for LGBTIQA+ families.

As works of art depicting pregnant bodies are limited you can imagine that exhibitions with this focus are also in short supply. They do however, exist. In 2020 the Foundling Museum presented Portraying Pregnancy.

And, in Dublin in about 10 days time Atong Atem, a South Sudanese artist and writer from Bor living in Narrm Melbourne will debut a new body of work titled Dust, curated by Catherine E. McKinley. Atem’s work is the main commission for PhotoIreland Festival 2023. The festival shared that Dust will be ‘be presented in The Chapel Royal, Dublin Castle. Dust will explore the relationship of Dinka women who act as mediums and custodians to the earth, to the rupturing history of Christianity and colonialism.’