New US Health Secretary, Robert Kennedy, has proposed a ban on welfare being used to buy soft drinks. The push back – thought to be paid ultimately by the soft drink industry – shows how money can be put to work in politics in the digital age.

But first, the policy context. In the US, welfare recipients have a portion of their welfare earmarked to a debit card that can only be used to purchase food. Colloquially known as food stamps, the card is already blocked from purchases of alcohol and tobacco.

Kennedy suggested that block be extended to soft drinks. The policy is unlikely to go nation-wide, as the food stamps program is run by the Department of Agriculture rather than Kennedy’s department, and also requires the approval of the states.

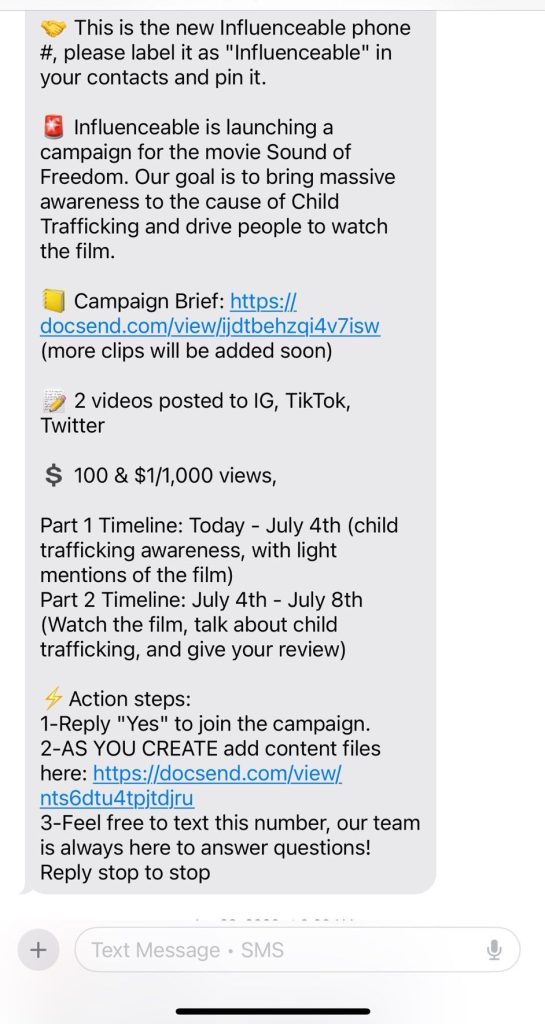

The debate nonetheless quickly spread over social media, under the moniker of a supposed “soda ban”. Several Trump-aligned influencers began posting about a “war on soda” last week. They all mentioned government or regulatory “overreach” and added in the choice fact that Trump himself is known to enjoy a Diet Coke. Screenshots suggest this messaging was directed by a digital media advertising company.

The interaction of influencers operating with the same messaging can have exponential effects on their exposure. The phenomenon has been described by University of Texas researchers as “engagement pods”.

The “war on soda” campaign was reportedly paid by the social media advertising firm Influenceable. Previous campaigns by Influenceable have offered hundreds of dollars per post plus a per-view bonus.

“Efforts to restrict soda purchases through food aid programs are a clear example of bureaucratic overreach that unfairly targets consumer freedom”, went the campaign pitch. The wording was repeated by influencers across X.

The Trump influencer network is tied into a tremendous amount of profiteering, with influencers hustling everything from life coaching to cryptocurrency to testosterone supplements. Yet cash for political messaging is also a bipartisan problem.

Previous reports have shown a contestant on The Bachelor was paid for abortion rights messaging. A TikTok star participated in the sponsored campaign “hot girls vote”. An NFL athlete was paid to advocate for gun control on his social media.

Such campaigns are sometimes referred to as “micro-influencer” or “nano-influencer” campaigns, as they bring together influencers with perhaps tens of thousands of followers each. These content creators are often perceived as more “authentic” and trustworthy than legacy media.

Relative to political advertising in the TV-dominated mass media era, the current situation reflects the fracturing of the audience. Rather than old-fashioned media barons deciding election outcomes, this means micro-influence and micro-payments to creator-contributors across the digital content stream.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter