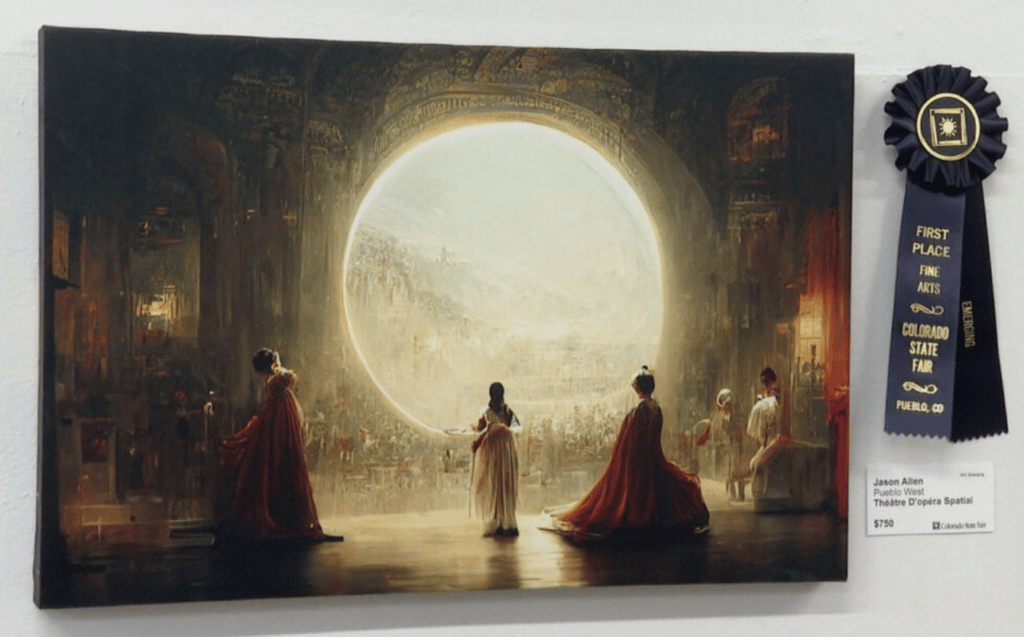

Jason Allen won first prize in the Colorado State Fair Fine Arts Competition with his work Théâtre D’opéra Spatial (French for ‘Space Opera Theatre’), he entered in the category of ‘Digital Arts / Digitally-Manipulated Photography’. Allen used an artificial intelligence program called Midjourney to create the piece, the technology turns lines of text (entered by Allen) into the hyper-real graphic we see before us.

Allen celebrated his win on Discord, stating ‘I have been exploring a special prompt that I will reveal at a later date, I have created 100s of images using it, and after many weeks of fine tuning and curating my gens, I chose my top 3 and had them printed on canvas after upscaling with Gigapixel A.I…I’ve set out to make a statement using Midjourney in a competitive manner, and wow!’ Allen is a game designer.

The winning work depicts several seemingly human and possibly female figures from behind, as if on stage, or in a parlour room while all individually preoccupied. A large circular window looms over the room casting a romantic light as it offers a view out to an indistinct landscape, is it mountains we observe, or some futuristic cityscape? It is reminiscent of an allegorical Renaissance painting, with notes of Gustav Klimt and, curiously, an air of science fiction royalty comes to mind.

In the wake of Allen’s win, social and international news media have offered a deluge of commentary, from praise to mourning the ‘death of artistry’. The artist was transparent about the nature of his process and it was understood and accepted by the Fair. The Colorado State Fair defines digital art as ‘artistic practice that uses digital technology as part of the creative or presentation process.’

The Colorado State Fair said on their Instagram account ‘The digital art category at the Fine Arts competition has people talking! At the Colorado State Fair, we think this brings up a great conversation. With advancing technology, the discussion of AI and art helps the Fair evolve from year to year.’ In the comments section that followed users raise interesting critiques, and also counterpoints about what it means to make art.

Jumping into the conversation in Australia, Dr Mike Seymour, a lecturer at the University of Sydney Business School, who last week facilitated the workshop ‘Design Thinking with DALL-E’ at DISRUPT.SYDNEY, issued remarks on the subject. Seymour shared ‘The issue of AI art may seem confronting, but the AI engine is just that: an engine. It makes no creative judgements – it does however respond to the ‘intent’ of the operator, or in this case, the artist. It is directly down to that artist to know how to guide the AI, what changes to make, and when to stop and say: I think this has artistic merit! I will submit it to an exhibition.’ Seymour presented the work of Andy Warhol and his Factory model as an example of artists conceptualising and supervising the creation of a work, in lieu of putting brush to canvas.

So with this in mind is the use of technology in the creation of art just another tool? It doesn’t appear to be a tool that can exist in isolation, as Gina Fairley points out in her recent article, quoting Kevin Roose of the New York Times, there is an issue to consider. Roose says ‘Apps like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney are built by scraping millions of images from the open web, then teaching algorithms to recognize patterns and relationships in those images and generate new ones in the same style. That means that artists who upload their works to the internet may be unwittingly helping to train their algorithmic competitors.’

Judges, Cal Duran and Dagny McKinley, spoke to the The Pueblo Chieftain in the wake of the controversy surrounding Allen’s entry and win. They said they were not aware the work was made using A.I., but that this detail wouldn’t have changed their judgement. McKinley also added that while she wasn’t sure where she stood on the new technology she said it ‘wasn’t going away’.