Did you know that about 100 years ago art was included in the Olympic Games?

The thinking was that astonishing athleticism was sure to inspire (and had inspired) some exceptional art, witnessing the best in human achievement would be a profound experience. Arguably art is in harmony with the concept of Olympism, ‘a philosophy of life, exalting and combining in a balanced whole the qualities of body, will and mind.’

Between 1912 and 1948, if you were an artist you were eligible to enter five categories from poetry to painting, architecture, music, and sculpture and hope to be awarded gold, silver or bronze medals as judged by creative contemporaries.

There was one caveat, your entry had to be inspired by sport.

This rule resulted in apparently a motley quality of submissions, motivations, and not a great number of them. It also unearthed critics and a judging process that wasn’t orderly, in the manner of sport. Sometimes a judge would not deem any work in their category as a prize winner, and it’s been said that on other occasions only a silver or bronze would be given out, with nothing tipping gold status.

Not many of the works from these few decades were preserved or collected for posterity and strangely all 151 medals awarded in the early 20th century (as the ABC has reported) were deducted from official national medial counts when the program was excluded from the Games in 1952, but some have been held proudly in national institutions.

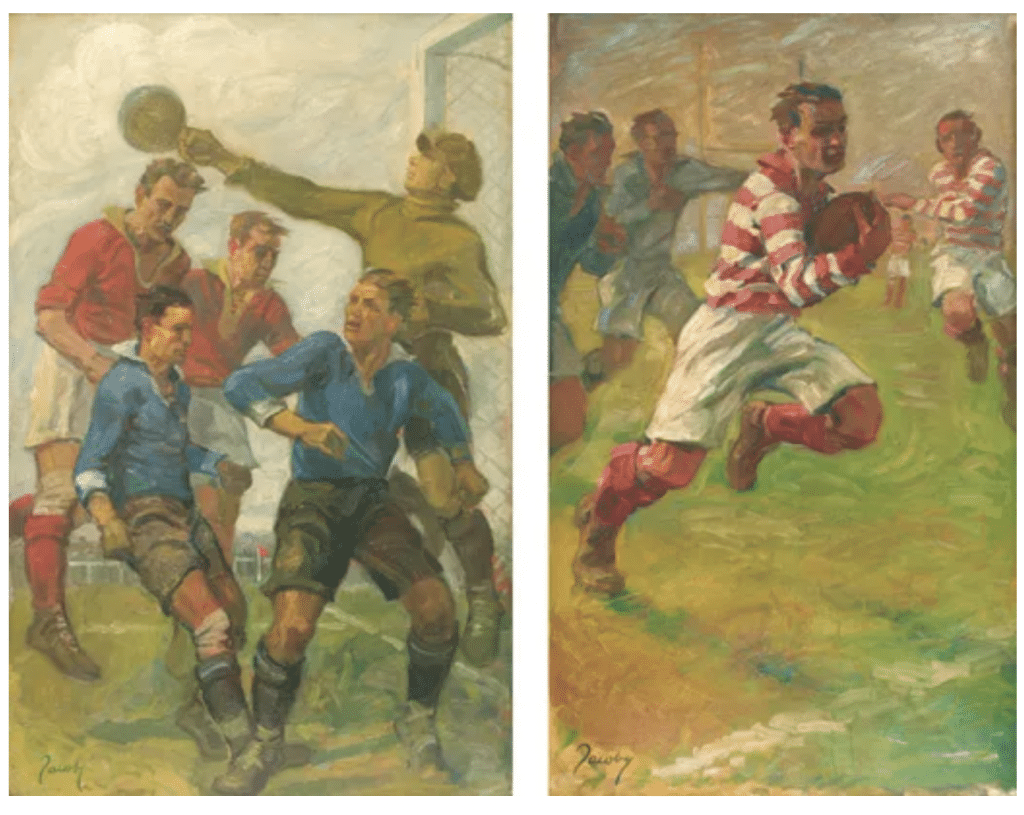

Take for example the Jack B. Yeats (1871-1957) painting The Liffey Swim, 1923 which is in the National Gallery of Ireland, and won Gold for Painting in 1924, the first medical Ireland won as an independent nation. The gallery writes that in this work Yeats ‘invites his audience to engage with the event by placing them among the spectators, who lean forward to catch a glimpse of the swimmers as they surge towards the finish line. The painting marked Yeats’s growing interest in Expressionism and his adoption of fluid brushwork and a charged palette.’ At the 1928 Olympic Art Competitions in Amsterdam, Jean Jacoby won the gold medal for a painting of Rugby, now in the collection of the Olympic Museum Lausanne.

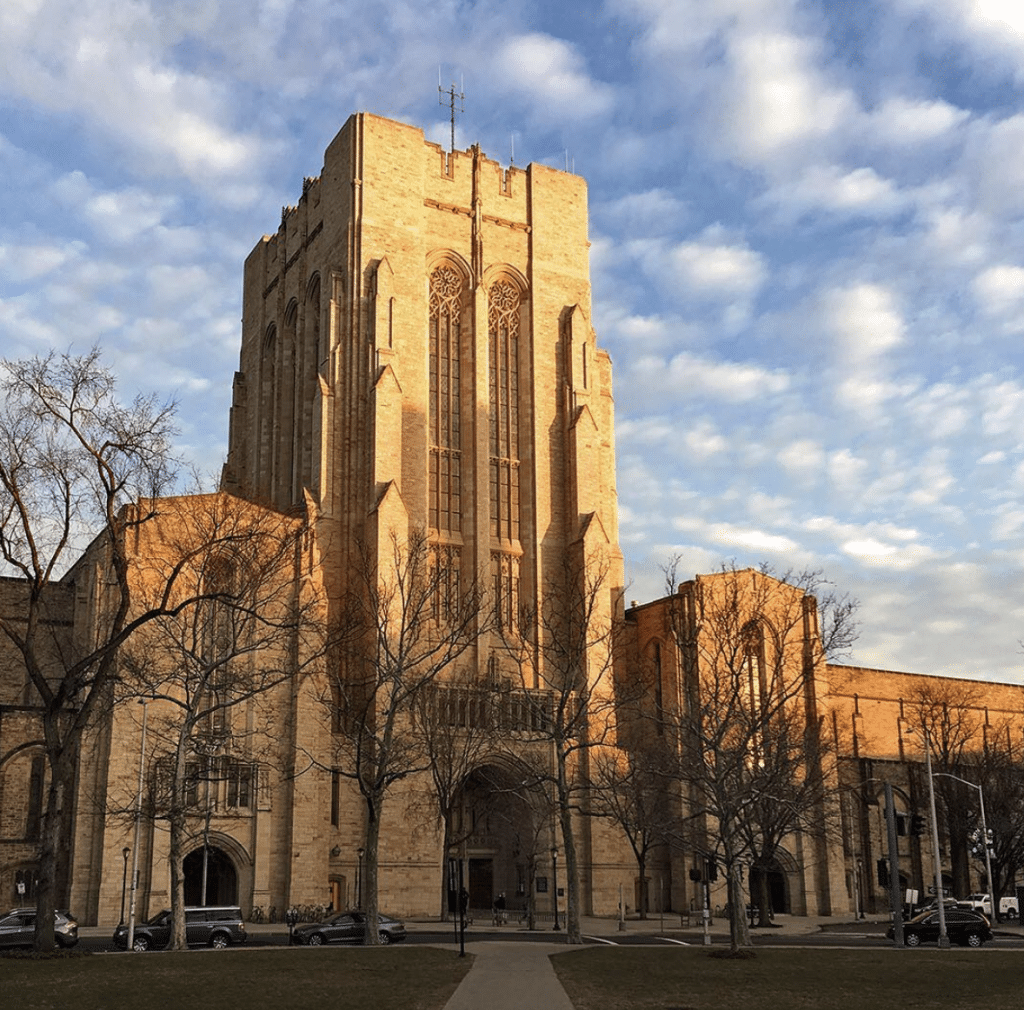

Architecture we still enjoy today is a result of the program, for example the Olympic Stadium in Amsterdam, designed by architect Jan Wils (Olympic gold in 1928) and Payne Whitney Gymnasium at Yale University designed by architect John Russell Pope (Olympic silver in 1932).

That all sounds pretty good, doesn’t it? Like fine dining and company, an apt pairing. But the party soured.

The downfall seems to have been the dissonance between a quantifiable or measurable feat, fastest swimmer or longest jump, and the subjectivity of art. Also, in the context of a meritocracy there were anxious thoughts; were artists using the competition for self-promotion? Was the judge of ‘good art’ truly impartial? The International Olympic Committee (IOC) rules stated and valued that the professional status of Olympic participants be amateurs, it would be a conflict to be a professional motivated by commercialism. As Joseph Stromberg writes organisers were wary of an ‘unwelcome incursion of professionalism.’

Politics were also an influence and a problem, for the 1936 Berlin Games the judging panel was heavy with German representation, platforming artworks that glorified Nazi Germany.

From 1952 to 2018 art was missing from the stage. Today, we have the Cultural Olympiad which is an art exhibition at the Games but there are no prizes, unless you count the sense of achievement and exposure in showing your work in the international ring.

This year the exhibit is taking place at Palais de Tokyo during the Paris Olympic Games run by the Olympic Museum in Switzerland. The artist-Olympians included in the show are Enzo Lefort, Annabelle Eyres, Grace Latz, Luc Abalo, Brooklyn McDougall, René Conception and Clementine Stoney Maconachie who is representing Australia. The former swimming star has always welcomed creativity as part of her life. Her gravity defying sculptures are inspired by movement, shapes and balance, you can read more about her personal journey with art and sport here. Stoney Maconachie is represented by commercial galleries overseas, and self-represented in Australia.