In Ancient Rome, politicians vied for popularity with gestures of food and entertainment – “give them bread and circus and they will never revolt” goes the maxim of 2nd century poet Juvenal. But in our new reality of daily isolation, bread has become an even more powerful symbol of livelihood. Forced into our abodes and our activities democratised to that which can only be done from indoors, the kitchen has become the place of comfort, sustenance and social peacocking. And bread, a symbol of thriving.

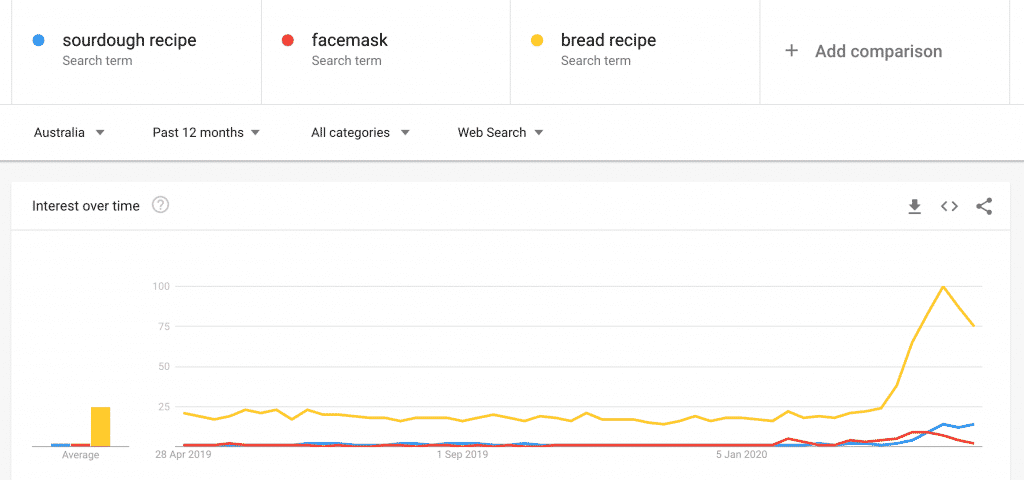

A freshly baked loaf of bread prior to COVID-19 was a niche hobby; a sourdough starter an unnecessary pet that required too much attention. But now, a warm boule of freshly-risen dough can fill the air with comforting aromas like an olfactory hug, and signify to the world that even in this time of struggle, we thrive.

The viral trends of cooking, and in particular bread baking, in isolation gives us unparalleled insight into how we as a society cope and communicate in times as strange as now. Eating bread symbolises that we are surviving – it says I can provide; I am fed. Baking bread from scratch shows that I am productive; I am thriving. In a 24/7 digitally-enhanced culture in which we are never truly “off” or alone, the pressure to be productive and deliver outcomes haunts us even into social isolation and into our kitchens.

But cooking in your kitchen – and baking bread in particular – offers also a conveniently modest way of humble-bragging that allows us to go to the edge of, but not over, the boundary of unsavoury crassness. As we grapple with the practicalities of social distancing, we have become hyper aware of class – having a stable home, job or family situation has been seen for the true privilege that it is, whilst unemployment rates climb towards the statistics of the Great Depression. In this time, it would be unseemly to flaunt wealth (à la Ellen DeGeneres’ tone deaf comment likening of isolation to “being in jail” from her $15 million mansion) or to be seen fleeing to your coastal beach property (as per now-apologetic, COVID-19 infected influencer Arielle Charnas or the now-resigned NSW Arts Minister Don Hawin).

There are reasons that bread-baking has gone viral and not caviar canapés or champagne ice-cream floats: accessibility and acceptability. The ingredients of bread are inoffensive and cheap – flour and water – and pose no potential to offend; it’s vegan, gluten-free adaptable, and is adored across cultures. The other precious ingredient is no longer a scarce commodity: time at home. Altogether, these aspects make for a low-risk investment with potential for very high return.

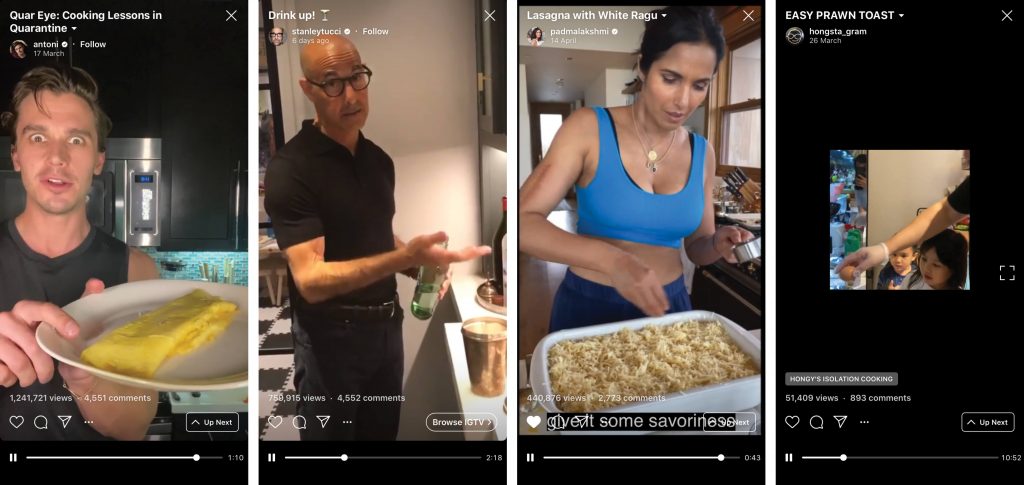

But let us not feast on bread alone. How our society deals with food is symptomatic of our culture’s adaptability as a whole. Now that we are forced to cook from our own homes, it’s food educators’ time to shine. Antoni Porowski from Netflix sensation Queer Eye – who was once roasted for the simplicity of teaching someone to “cook” guacamole – was one of the first to launch a series of Instagram lessons entitled Queer Eye: Cooking Lessons in Quarantine, which have receieved almost 10.5 million views to date. On the homegrown front, Merivale chef and host of SBS’s The Chef’s Line Dan Hong has charmed the masses with homemade recipes for prawn toast and “Australia’s national dish that is salt and pepper squid” (complete with commentary from his children). Of course, staple cooking oracles such as Bon Appetit have increased their tutorial output to accolades (in case you want to get ahead of the trend, they’ve stated that spring onion pancakes could be the next sourdough). And, those who have built their brand on home-cooking, such as Alison Roman who penned Dining In and Tin Can Magic’s Jessica Elliott Dennison, are now in the limelight.

But for brick and mortar restaurants, pivoting has presented much more of a challenge. These cafes, bars, fine dining institutions and food trucks are the canaries in the coal-mines of our isolation economy, along with the many supply chains and casual workers they represent. The food industry is at the mercy of our consumer appetite – on one hand, panic-buying sees supplies fly off the shelves, but concurrently the lack of demand in other parts of the industry has resulted in unplanned wastage (Dumped Milk, Smashed Eggs, Plowed Vegetables: Food Wastage of the Pandemic). Across the world, ride-share drivers have become food drivers, and food drivers evermore dependent on the flawed gig-economy. With no respite in sight, beloved businesses have closed their doors permanently. Others have been able to adjust to home-delivery or take-away options, as business-owners the world over bend backwards to re-frame their brands and meet regulations.

It’s a circus indeed, if ever we did see one. There’s our politicians as the grand showmasters, trying to provide some semblance of control; trapeze artists flipping and free-falling through the air; and an ever-present cacophony of drama that makes you anxious in the stomach but captures your gaze. It’s no wonder in times like this, we turn to our most trusted carbohydrate companions: we turn on the oven and ready the butter and comfort ourselves that even in times of struggle, with a piece of toast in hand, we can – somewhat – thrive.