As a heatwave hits the east coast, it’s not just the weather but also that smoky eucalypt smell that tells us it’s summertime. Widespread hazard reduction burns around NSW in particular have brought bushfires back to people’s minds after a COVID and La Niña-induced interlude.

Hazard reduction burns are meant to reduce the forest’s “fuel load,” making bushfires less severe and less likely. But recently, some environmental scientists are more vocally arguing that this conventional approach is counter-productive.

Associate Professor Philip Zylstra criticised the “reduce biomass” approach in a 2022 paper.

To test the hypothesis, Zylstra’s team studied a 55-year database of forest fires in south-western WA. The study found that, in this bioregion at least, the forests least likely to burn were those that had gone the longest without being burned.

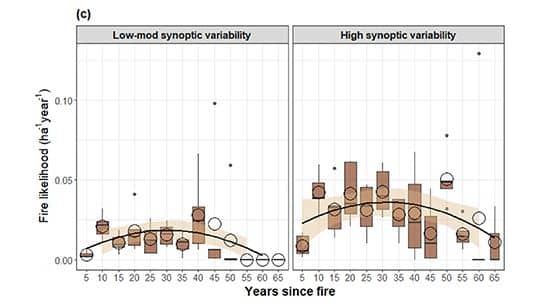

What this means is that, in this bioregion, hazard reduction burns (or uncontrolled fires) reduce the likelihood of subsequent fires for 5 to 10 years. But the dense regrowth that follows then increases the risk of fire, peaking about 25 to 30 years after a burn.

“Disturbance by (predominantly prescribed) fire promoted a ‘pulse’ in wildfire likelihood lasting some decades but which then decreased and remained low in long-unburnt forests,” said Zylstra.

“Flammability is affected by the interaction of multiple factors, including the proximity of foliar biomass to the ground, its continuity to the canopy (ladder fuels), the flammability of component plant species, and the microclimate of the forest.”

After 30 years, these mature forests “self-thin”, as sunlight to the forest floor is blocked. This means there are less “mid-storey” plants that can cause fire to ascend within the forest.

The forest crown also reaches further above the ground and becomes denser. This causes the forest to retain more moisture and be more sheltered from the winds that spread fire.

These findings vindicate an established point in indigenous cultural burning. “‘Aboriginal fire knowledge is based on Country that needs fire, and also Country that doesn’t need fire. Even Country we don’t burn is an important part of fire management knowledge,” says Victor Steffensen.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter