Integral to the outcome of a photograph is paper, light and process. ‘Catherine Rogers: Evidence and The Visual’ at ANU’s Drill Hall Gallery (DHG) in Canberra is the first survey exhibition of work by photographic artist Catherine Rogers, who since the early 1970s, has continued to explore her interest in photo-based media using a variety of techniques and technologies.

Rogers explores what photography is and what it can do through her investigations of both the limitations and possibilities of the medium.

Her depictions of land and forest, seascapes, definitive horizons, endless skies, space, and the historical built world not only meditate on the beauty and awe of the natural world but at times question the ethical, moral, and ecological issues at hand.

Bringing together a large body of work produced over the course of four decades ‘Catherine Rogers: Evidence and The Visual’ catalogues the artist’s use of silver-based and digital media, lensed cameras and pinhole cameras, as well as images made without the use of a camera – in the vein of English scientist and innovator of photography William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877).

In 1834, driven by his own frustrations with drawing Talbot experimented with ways to transpose what the eye could see onto paper. Using chemical emulsions of salt then silver nitrate he made light sensitive paper, on which, he placed objects such as plant cuttings and exposed them to the sun. The paper darkened while the plant or object blocked light from reaching its underneath resulting in a reverse impression of the subject on the paper. These became known as photogenic drawings, the first photographic negatives. Also drawing on his expertise in optics Talbot furthered his explorations using homemade cameras and pioneered the first negative to positive photograph process.

“Talbot’s 1835 negative of the oriel window in his ancestral home, Lacock Abbey in England, is one of the most intriguing images in the history of photography,” says Rogers. “To create his photograph, Talbot placed a small, wooden, light-tight box with a lens, on a table directly in front of the south-facing window; the camera was, effectively, ‘looking’ directly into the sun. It is an image about light and its origins, and was part of Talbot’s inquiries as to how and where light emanated from that could enable an image to be made.”

The exhibition showcases numerous series of works including Between Heaven and Earth, Lost in Space, 2021, a selection of unframed images on A1 cotton rag paper that direct our gaze beyond Earth to the surface of “the moon, the sun and the universe, planets, further suns, stars and constellations, space, heavenly things and celestial events.”

Drawn from Rogers expansive image archive the photographs on display in Details of the World Part 2, 2018, which includes Rogers 1997 (negative) image of Talbot’s latticed window, “allude to aspects of what generally passes for a visual history of photography, about the photographic image and its relationship to the world it seeks to picture,” Rogers writes on the exhibition room sheets offering insightful details about the origins of photography and the works on view.

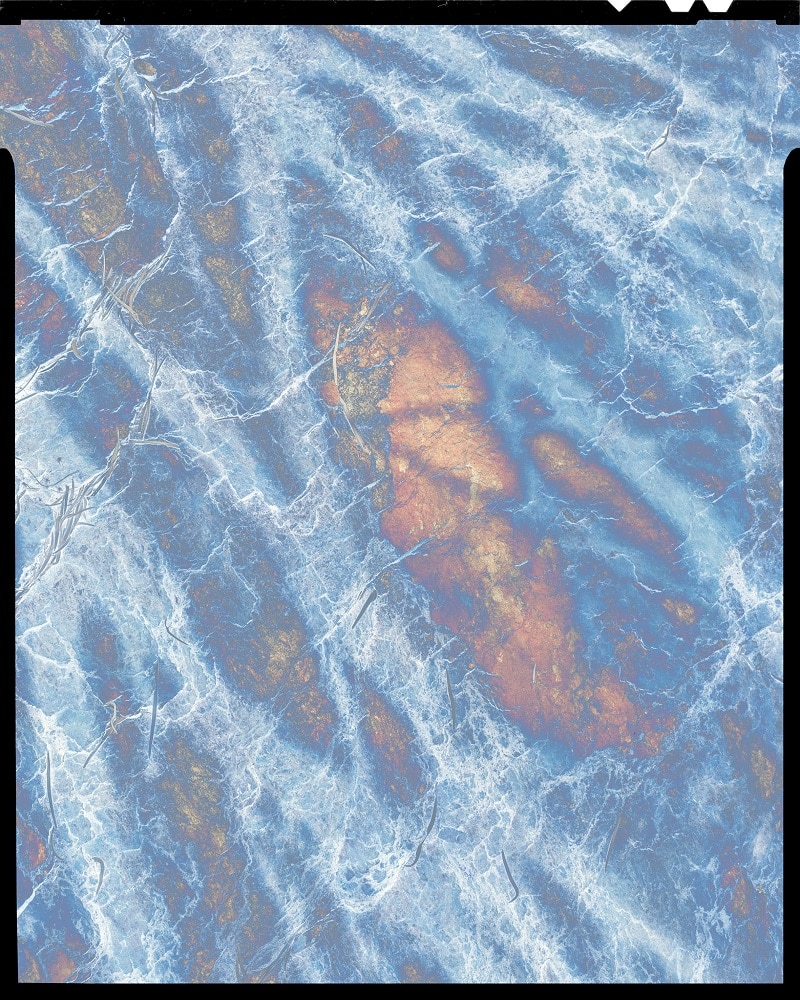

The Red Road: Upper Florentine, Tasmania, logging coup F044A, 2007 series is the outcome of the artist’s mission to document two of Tasmania’s threatened ancient forests before they were destroyed by logging and literally turned into wood chips. Rogers took photographs of the giant rainforest trees including myrtle (Antarctic beech), sassafras, leatherwoods, and celery-top pine, as well as huge radiant tree ferns (Dicksonia antarctica), and the forest’s delicate eco-systems, flowers, fungi, lichens, mosses, tiny ground orchids, and leaf litter that grew in the precious Upper Florentine Valley and Styx Valley.

In Nature of Evidence, 1986 Rogers expresses her concern for the photographic evidence produced in the Lindy Chamberlain case. “Photography and photographs of all kinds played a crucial part in the trail of perceived evidence,” says Rogers. “Can a photograph made in 1/500th of a second convey anything about anyone? Photographs of Lindy Chamberlain’s face were thought to be able to reveal something about her and the nation scrutinized these images of her daily in the media. There is an idea that photographs are real proof that they provide irrefutable truths. Photographs, however, only introduce more conjecture,” she adds.

“Underlying everything in Catherine Rogers’s work is the question of the evidential – whether a photograph tells the truth, is bogus, or generates doubts and unease about its veracity. And underlying everything is a quiet note of exaltation – a lyricism that revels in spaciousness, in refinement of tone, luminosity and clarity: in the beauty of things that are wonderfully well seen,” the gallery shares.

Drill Hall After Dark – Artist Talk: Catherine Rogers will be in conversation with Emeritus Professor Denise Ferris and Associate Professor Martyn Jolly on Wednesday 10 August, 5 to 8.30pm.

‘Catherine Rogers: Evidence and The Visual’ is on until 14 August. Drill Hall Gallery is located at the Australian National University, Kingsley Street, Acton ACT 2601. Entry is free and the gallery is open Wednesday to Sunday, 10am to 5pm.