At the end of my last piece “For want of a coffee can, we left $7 million on the table,” which covered the story of Equities and Freeholds Limited (EQF), I suggested EQF was akin to the 2005 movie, “Batman Begins”. It had a sequel, a far better and bigger movie. “Dark Knight”, the finest work of Heath Ledger.

And EQF has a much “better”, bigger and way, way more expensive sequel too. A $25 million one. When you read the story, you might indeed think it’s a dark night.

Of EQF’s 2,910,506 shares which should have increased in value by $7million or so from $0.37 to $2.86, if only the portfolio had remained in a coffee can between June 2009 and December 2019, 2,517,433 (86%) of them were owned by ONE investor.

I know that investor intimately. It was called Tidewater Investments Limited (Tidewater), and it was listed on ASX. I was the largest shareholder and Executive Director running the show, with just over 30% of Tidewater’s shares. Tidewater is now Australian Rural Capital (ASX: ARC), has a market capitalisation of just over $3 million and is the second largest shareholder of Namoi Cotton Limited. Tidewater did distribute to shareholders certain of its holdings (INQ), which they have done very well out of, and pay some dividends. But it sold off other holdings far, far too early. So this is the story of EQF’s “parent”.

It’s a great lesson to actually look at what the cost of not being patient has been. Not many folks do, it can be searingly painful, and the numbers are often quite staggering. This is your chance to learn from me – free of charge! – what the cost of trading and impatience really are, versus the benefits of half-decent (but not outstanding) stock picking which is allowed to compound.

We used a piece by Robert Kirby from 1984 (“the Coffee Can portfolio”) in our first article, and noted the presence of a multi-bagger security (one which appreciates many fold) within a portfolio, and the offset to others even where there is significant or total loss. Of twelve securities directly owned by Tidewater, three (25%) eventually went broke, albeit we received consideration for one of them prior to that fate. There is no survivorship bias in this analysis.

Tidewater had some other business at the time, notably two AFSL’s and hence had staff overhead which arguably forced our hand a little. Those businesses made real losses, but that’s not the focus for this article.

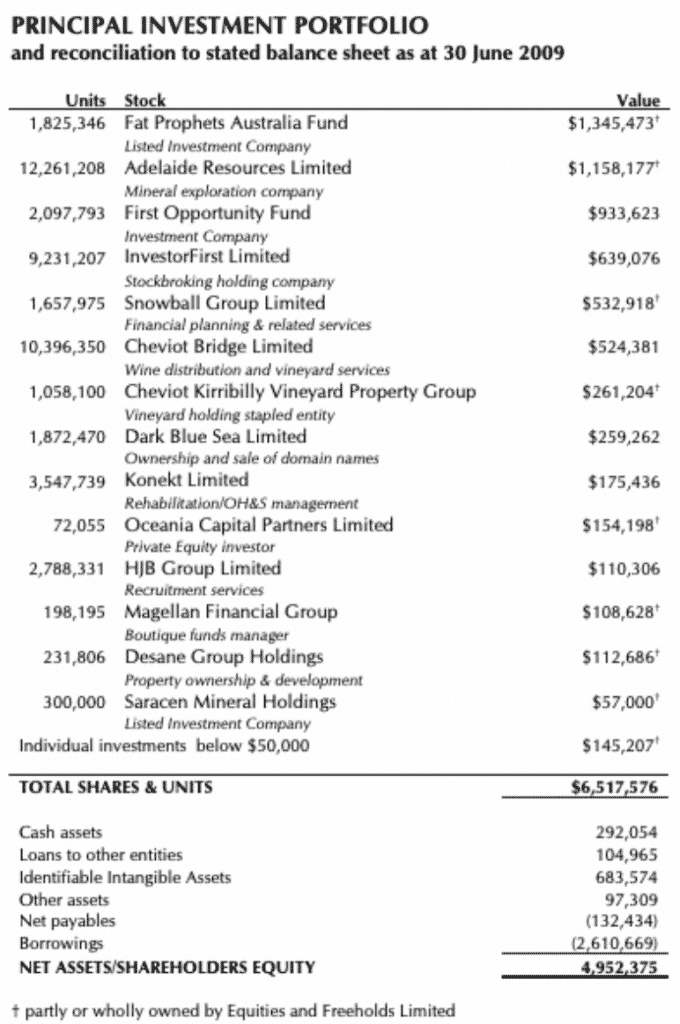

The snapshot of page 6 of the Tidewater report for 2009 containing the portfolio is shown below. The sword super-scripts are important because part or all of the relevant holding where applied was owned by EQF and so needs to be deconsolidated from the portfolio, and EQF reinserted to show its benefit. There are a few other minor bits of accounting jiggery-pokery but nothing which in any way impinges on the story.

Most folks would think it’s a fairly motley set of investments, but there was some method in the madness, notably that the stake in First Opportunity Fund represented over 20% of that company’s capital which gave us a small amount of leverage over what was to come. It was a free option with some smart investment bankers backed by a minor discount to NTA:

The two Cheviot’s both went broke – it’s usually better to drink wine than invest in it. However, many readers will be unfamiliar with the names of companies in the list. When you look at the later table, two will reveal themselves as spectacular back-door listings, but backed by assets or businesses.

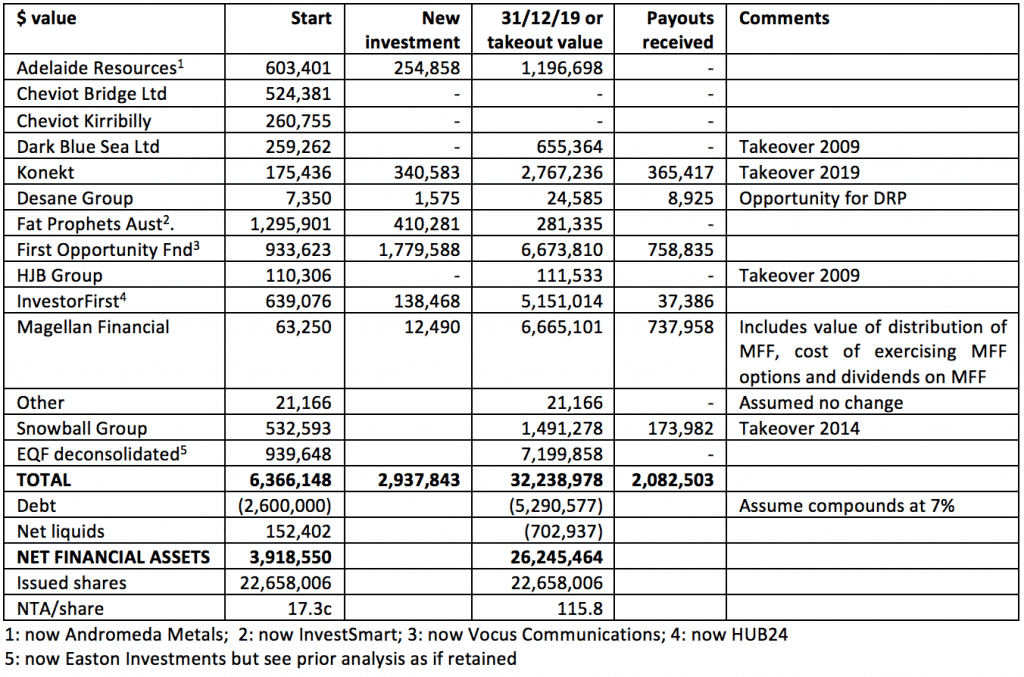

The analysis which follows again assumes that we took up entitlement issues for each company (good or bad) but did not reinvest dividends where available. That disadvantages the analysis for EQF quite severely. I have hypothesized capitalizing interest on the debt at 7% to get a “bottom line” but there is no other adjustment for the time value of money, nor for the not insubstantial expenses which would be incurred in running a small ASX company. So it’s best to just focus on the portfolio values.

More importantly, we have NOT used peak share prices to sensationalise the assessment. One of the holdings (be patient!) has a closing price on 31 December 2019 of $2.86 versus a peak price of $9.25 and a taken up rights issue at $7.55/share. Magellan obviously has been higher post 31 December 2019 and even in the period considered, did trade over $60.

From a starting value of $6.366million, between 30 June 2009 and 31 December 2019, we would have been required to invest a further $2,937,843 into the portfolio, the majority as late as 2017; however, the capital value of the portfolio would have grown from an effective $9.3 million to $32,238,978. We would have also received dividends and cash capital returns of nearly $2.1 million. A $25 million return.

Once again, as in EQF, Magellan is the star performer, but far from the only one. But there are three stark lessons once again, by allowing the investments to compound:

- There were four takeovers, one of which, Konekt was at a startling premium;

- One investment, Vocus (nee First Opportunity Fund) if sold closer to its high price would have yielded over $20million alone and increased the portfolio value to over $46million – but that’s not what the coffee can portfolio assumes (you’d have been bloody tempted to open the lid though…..);

- As we discussed in our first article with Adelaide Resources and its wide price fluctuations, you have to be prepared to let the investments gestate. Three years in, from a starting price of 7c, in mid 2012 InvestorFirst is having a 1-1rights issue at 1.5c and the board seems to be changing monthly. It since had a 40-1 consolidation so the average entry price into what’s now HUB24 if retained is ~$1.68/share.

Why have I done this and what can we learn from the lost $25million?

To the best of my knowledge, this is a unique attempt to look at the return available from a quirky but publicly disclosed portfolio, had it simply been retained and not traded. As a consequence, rather than just saying that a person collected share certificates over a period without disclosure of what and when, this piece deals directly with that facet. It’s also a more powerful and emotive message, in my view, than a successfully retained portfolio.

I have done this analysis because I obviously know the background to the story intimately, it’s a little bit cathartic, and it helps me directly to do better in the future. Nothing is hidden.

However, I also feel that where trading is global, cheap and instant, younger investors should step back. It’s the perfect time to do so since we have had a correction in stock markets, but also seen companies face up to a stressed environment that they had largely never seen. That gives you the chance to assess them when they are in the worst possible (temporary) shape, and evaluate downside risks you would reasonably have never thought of.

You may feel equity markets have bounced a little too hard from their lows of mid-March 2020, but under this type of analysis, that doesn’t matter too much. If you think that way, you may get a better chance down the track; alternatively, you may not. But what you will get is the chance to evaluate companies in a manner never seen before.

For example, you see companies with fabulous stand-alone long term assets which are temporarily closed or operating way below capacity, but where the franchise is lengthy. I cited Madison Square Garden in the original article but think Sydney Airport, Star City, Treasury Wines and others. Will these companies suffer permanent impairment? What about others which may not have great businesses but are extraordinarily cheap as a result of share price dislocation, but where you may have to wait for a corporate event for the value to be liberated? Unless you “lock it up”, you’ll get bored waiting. Guaranteed.

So the lesson is simple. This is the best time in over ten years to undertake this exercise. Find the best businesses you know, re-evaluate and if you feel it’s reasonable, buy a modest amount and put the holding certificate in a coffee can under the bed. Keep doing it. Don’t sell, unless you receive a takeover bid – choose well and you will. Open the can in ten years.

Learn from my mistakes how to do it properly and the type of obstacles you will have to face to do so. But in the most practical of ways, I hope I have shown you that the rewards for being patient, not trading, and letting your positions run can be remarkable. And by reinvesting the dividends, they are magnified.

However, pick carefully. Doing my tax the other day, I saw I had held NAB for five years, reinvested every dividend and eventually sold at $28.14. I broke even. At the time of writing the shares are $16.39. Adverse structural change and/or apathetic boards and crap culture are not coffee can candidates. Monopolies, unique businesses and passionate beyond belief management assuredly are. Go find them.