Productivity in the housing construction sector has gone backwards since 1995. That’s the striking finding from a fresh report from the Productivity Commission released this week.

The Commission researchers, led by former Grattan Institute CEO Danielle Wood, found fundamental issues impacting housing supply. Since 1995, the ratio of dwellings per construction-worker hour worked has fallen by 53%.

This can be adjusted by factoring in the value of the dwellings constructed, to take into account better and larger construction. Houses are on average 25% larger than they were in the 90s.

Yet even on this metric, value per hour worked has fallen 12% since 1995. Keep in mind that the average worker across the economy as a whole produces 49% more value per hour than the average worker in 1995.

This couldn’t come at a worse time for house prices. As Alan Kohler recently pointed out, record migration may have over 600,000 extra people looking for housing in FY25. Moreover, in the words of the Commission, “Very few recent migrants work in the sector.”

So what’s the problem with housing construction? The issue seems to lie more with houses than apartments. House construction value per hour worked has fallen 25%, while apartment/townhouse value per hour has increased by 5%.

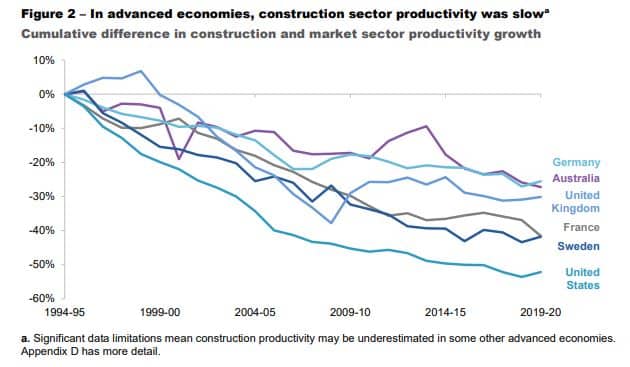

The poor output in construction is an issue across the Western world.

It would be unsurprising for construction productivity to be relatively low compared to other sectors. Construction is sui generis, with little potential for standardisation. It’s also an industry with lots of small companies, who are unable to fund large research & development spending.

But the Productivity Commission lays the blame for the decline in productivity at the feet of government. Construction managers have to grapple with literally thousands of pages of planning regulations. In Queensland, for instance, builders have to consider 17 different acts, instruments, plans, policies, provisions, guidelines and strategies, in addition to the 2,000-plus page National Construction Code.

Builders must navigate approvals from local governments, utility providers and state-government departments. Moreover, because these approvals are needed in sequence and the different regulators don’t speak to one another, builders end up de facto coordinating the work of government as well. Over the past 30 years, white-collar construction employment has grown twice as fast as blue-collar employment.

In sum, standardising and streamlining approvals, which in many cases these days take over a decade, is the most pressing need for alleviating the housing crisis. So far, the major parties have been more talk than reality on this issue.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter