Sydney-based artist Steve Lopes is a figurative painter whose practice spanning three decades continues to inspire his exploration of the human condition and our movement within the landscape. Through his choice of oil paint as medium Lopes manifests the innate sensibilities and characteristics of our existence. He skilfully captures the human form in those ‘movements-between-movements’ that might ordinarily go unnoticed. A bend or twist in the body, a gesture of the hand, a tilt of the head.

Lopes paints moments of contemplation and activity that become quiet junctures in time, stilled for observation, rousing an evocative sense of familiarity that connects us to our own existence.

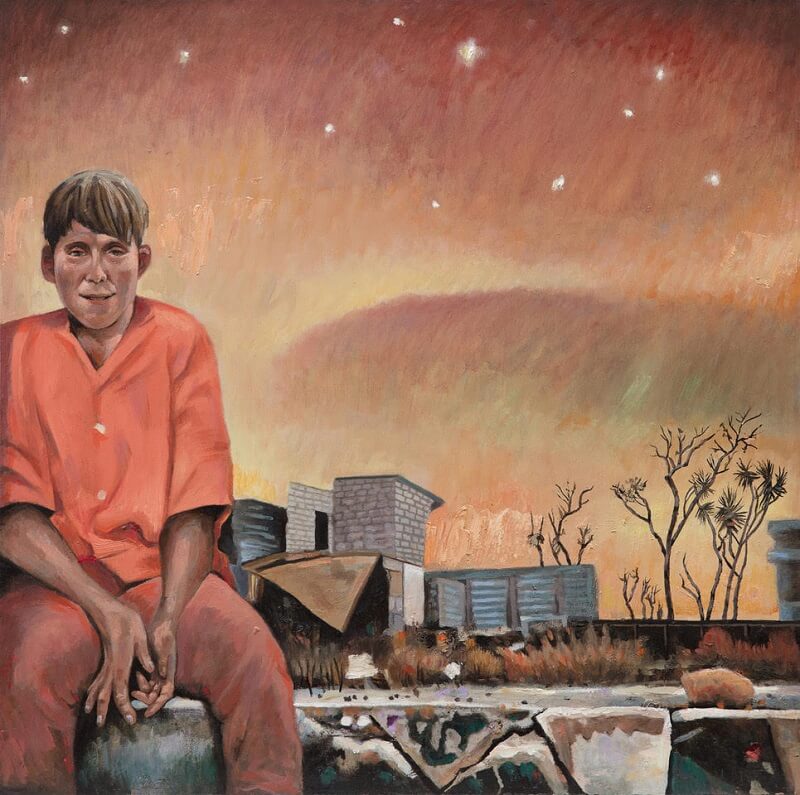

In his latest exhibition ‘Sans Souci’, which is on at Stella Downer Fine Art in Sydney’s Waterloo, Lopes presents a series of new paintings, drawings and collages created during the pandemic of 2020. The title of the show ‘Sans Souci’ borrows from the French expression meaning ‘without care’, or as Lopes puts it ‘no worries’. This seemingly nonchalant utterance has a kind of playful tension to it. Lopes says, “If people come and have a look, they’ll notice there are no heavy themes to it, it’s almost joyful to some degree, but there’s also an element of what’s happened in the last year and a half to everybody.”

I spoke with Lopes prior to visiting the show, which is on display until 1 May. Here’s what he had to say about becoming an artist, his practice and the feeling behind the works in ‘Sans Souci’.

How did your journey to becoming an artist begin?

I’ve always known I was going to do art. From the age of four or five I remember copying comics. Coming from a migrant family we kept to our Italian community, I lived out my days through drawing, reading and copying comics. I’ve always loved drawing and through school that’s all I did. After school I studied painting at COFA College of Fine Arts, it was called City Art Institute then. To get myself through college I worked as an illustrator for the Daily Telegraph and The Australian. Working at the papers taught me about deadlines, finishing work and being diligent. I’ve never not done art, or had to think ‘is this going to be my career?’, it just always was. When I was 24, I gave it everything and became a fulltime artist. I went overseas and studied in England. I looked at artworks all around Europe and learnt more from looking at paintings in major museums than what I was taught. I painted and did a lot of commissions in London and came back to Australia to set up my practice when I was 29. There was never any question that I was going to be a painter.

Why have you chosen to work in oils and is there a sense of ritual in the process of making your own paint?

Yes definitely. I do make my own paints and I work early on with tempera, which I make from scratch using egg in the mix. I love my history in my painting, and oil paint has got a rich history. I almost feel like an antiquated artisan in a way, because technology is moving forward, but there is a real method and chemistry to oil painting. It’s hard to understand, but it’s one of the most beautiful mediums to work in and it’s really difficult. I learnt it over-time and I love it. It comes naturally to me and I devote myself to it. Acrylics dry flat and they don’t have that certain colour that I’m after.

Your work conveys an interest in the human condition, the landscape, and our relationship to it. Where does this come from?

I generally like people and I think my insular background growing up in a migrant family made me notice the differences between coming from an Italian background and Australian ways of life. I didn’t really fit in to either world. I wasn’t in Italy and I wasn’t Australian fully. I probably had difficulty making friends early on, so I was a bit more internal. You live between two worlds, you realise it is a big world and you look for similarities. I travelled a lot when I was young. I went to New York and I started to see similarities between people everywhere. I did residencies in China and I went to Gallipoli and basically people are people.

I think there is a universality in my work, which I like. That is a conscious thing, I don’t try to put too many markers on a particular place if I can avoid it. I like drawing and family life and I just want to express what it is like to be human. I think that comes out in my work.

What is your process for bringing new ideas to the canvas?

They come to me in dreams surprisingly. I have an idea of what I want, and everyday stuff just sits there for a while. I do a lot of collage, and drawings of family members and I paint plein air. All of a sudden, I’ll think that family member would go good with this landscape. And then putting a weird object in the middle of a collage inspires me to put that as a painting. So, there’s a whole range of things. I try not to have any one way of working. I try not to make it too formulaic.

I take photos and I have a sketchbook with me everywhere I go. I refer to everything, it’s almost like a fertiliser. Everything I see is a background of images and ideas and they all come out strangely. My works are a mix-match of all of my influences coming into the work.

How do you know when a artwork is finished, is it both visual and intuitive?

Yes very much so. I think you get better at it, as you get older. But if a work goes too quickly then I tend to be quite suspicious of it. I need to have a bit of a fight with the work, there needs to be a lot of surface qualities that need to interest me. I labour over my works and as I get older I’m more patient and can leave them sitting there for a couple of years and have a batch of works on the go, not trying to finish anything. Then all of a sudden everything gets finished. If I’m happy for it to leave the studio door and I feel comfortable, then that’s a marker for me. You never really know, but there comes a point where you just have to let it go.

Tell me about the title of the show is there a dichotomous intention at play here?

Yes, it’s tongue in cheek. There is a playfulness to the work, there’s also some kind of hidden message. There is a painting of a woman walking in the bush and it’s a beautifully painted background, very joyous. She’s got her hand over her face in a way that almost looks like she is troubled, but the bush allays those fears in the background with that playful quality of the paintings. That adds a tension to the work, and I am trying to get that across, but there is a light colour in the show. I’ve made it sort of the joyful colour and I’ve tried to play with that dichotomy. I think you’re right, there is something going on, which is a bit different from what I’ve done before.

I made a conscious effort to use more colour. It was quite dark times for everybody and I wasn’t interested in doing dystopian works during that period. I wanted to have some positivity to what I was doing. I do think that changed some of the works, and the mood made me conscious of what I was doing.

Your figures are often posed in awkward positions can you explain this?

I try not to do the most obvious pose. It can affect the electricity or the charge in the work. I have studied a lot of the older painters like Goya, Salvatore Rosa, del Francesco, the Italian school. If you look at their works there might be a tiny finger out of place, a toe pointing upwards, or a figure tipping over. It adds a strangeness to the work and you’ve got to force it until it almost looks ugly. In a way that makes the human form interesting. If you just take that little extra step with figure placement you can make them look really interesting. It might be sticking a leg out a little more than what is comfortable. That’s what makes people keep looking at the work over time.