On 9 July 2020, a positive coronavirus test result was returned for a staff member at St Basil’s nursing home in Fawkner, Melbourne. Three weeks later, the facility was deemed so unsafe that every one of its residents was medically evacuated to hospital.

How this came to be is the subject of an independent inquiry released one month ago, and now a two-part summary for A Rich Life. Having just read the document, I apologise to readers for leaving this astonishing report unattended since it was released on 30 November 2020.

What Went Wrong at St Basil’s Nursing Home?

Problems at St Basil’s began to mount immediately following the 9 July positive test result. The result was communicated to the local public health unit and Victoria’s Health and Human Services department, as well as a NSW-based contact tracing team (with Victoria already suffering hundreds of new infections per day at this stage).

Yet it was not until 14 July that the Commonwealth Department of Health was notified. Mass testing of all residents and staff took place on site on 15 July. By the time all results were known a few days later – more than a week after the initial positive test notification – 33 staff and residents were already Covid-positive.

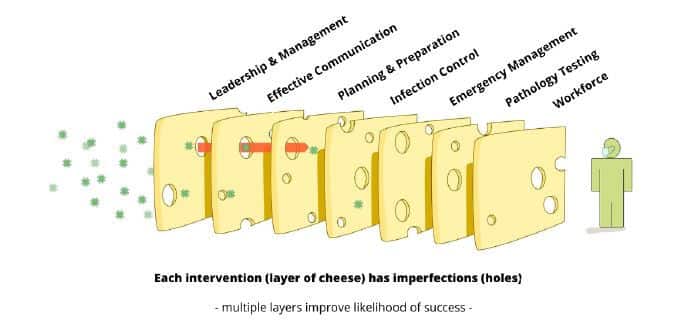

The rapid spread in the first week goes to show the tremendous challenge of countering the SARS-CoV-2 virus, even with experienced and trained staff. Partly this is due to the highly infectious nature of the virus itself, but also the particularities of the aged care setting: recirculating air, close contact, and a large population of vulnerable people interacting with one another.

These obstacles, however, were soon multiplied exponentially. Follow-up testing conducted on 19 July found the number of infected residents and staff had risen to 65 people (out of a total 117 residents and 120 staff). In response, Victoria’s Chief Health Officer made an ostensibly sensible decision based on Covid-19 evidence and best practice. It was a disaster.

On 22 July, his public health order came into effect: “All staff who had been in clinical areas at St Basil’s for two hours or more, cumulatively, between 1 and 15 July, would be designated as close contacts and required to self-quarantine for 14 days.”

This applied to every single staff member at the nursing home, including senior staff and management: a full stand-down. Diplomatically, the inquiry notes that the Aged Care Quality and Safety Commissioner “supported a more nuanced response.”

The chairman of St Basil’s strongly opposed the move, and refused to comply without an explicit public health order, which was then made. St Basil’s response was published on their website the same day: “We note that our entire leadership and management team will be completely sidelined so it cannot be said that we are in control or managing the facility during this period as we will not have any supervisory or oversight input whatsoever.”

This comment itself reveals a miscommunication, as it had been suggested the old management would remain on call to answer replacement staff queries. This did not eventuate; their queries by phone and email largely went unanswered.

And so a trained and experienced workforce were replaced by a cohort of senior staff and managers with little or no experience in aged care, who themselves were left to supervise labour hire firm-supplied staff with no experience in health or aged care, and little to no English. As we will see in Part 2, chaos ensued.