A global pandemic, the world’s largest iceberg breaking away from Antarctica, and now a mouse plague, with a locust plague expected hot on its heels. The 2020s just keep getting better.

Yes, there really is a mouse plague hitting country Australia, caused by the record, drought-breaking rains leading to bumper summer crops. An unprecedented amount of land is expected to be under cultivation when this year’s winter crops are sown in August, and this is great news for the mice.

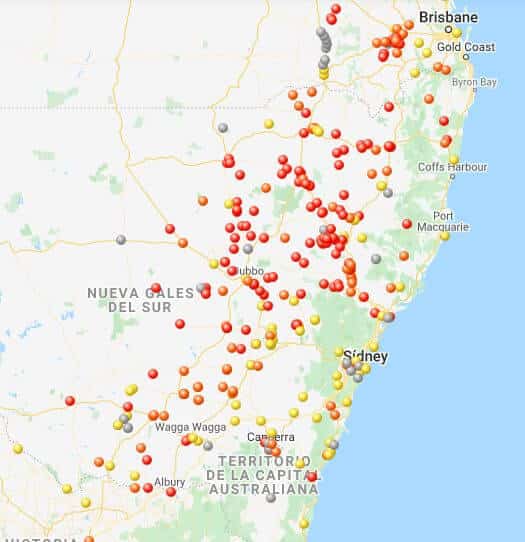

A wiki-style web-page, Mouse Alert, is tracking mouse sightings across the country. For its part, the CSIRO issues a Mouse Report, which says mouse numbers are “moderate to high” in many regions of southern Queensland, northern, central and southern NSW, northwestern Victoria, parts of South Australia and around Ravensthorpe, WA. This is a major concern, because mice continue to breed through autumn and their numbers do not peak until late August.

A survey of NSW farmers found all farmers had been spreading mouse bait. Ten percent of farmers had already spent more than $50,000 on bait, and some much more.

But first-hand reports suggest it’s been much more than a “moderate” situation to live through already. A Dubbo supermarket worker told The Guardian they regularly dispose of 400-500 poisoned or trapped mice every morning before opening the store. Residents also described fridges regularly breaking down as mice try to get in and die in the machinery.

News Ltd quoted a piggery farmer at Wynarka saying that there are now so many mice and they are so hungry that they are attacking his pigs. One family left their house unattended for four days, and came home to thousands of mice inside. Another sieves 100 mice out of his swimming pool each morning.

What’s the solution? The state government is currently distributing 5,000 litres of the normally prohibited bromadiolone. Its use has been criticised by ecologists, however, because the pesticide is highly toxic even as it passes up the food chain to animals like birds of prey that feed on the mice.

Earlier plagues have seemed to end as suddenly as they began. High mouse population numbers and a lower availability of feed at some point cause them to gruesomely turn on each other and eat their young, such that the population quickly collapses.

Locals are praying for days of flooding rains to wipe out the rodents. But with climate change, a lesser number of morning frosts each year favours the mice’s survival.

Maybe the Mayans were onto something when they identified the end of the world with ‘12. They just had the numbers back-to-front.

Follow Christian on Twitter for more news updates.