If, like me, you were educated in the 1990s – when the Keating government was leading modern Australia through its first baby steps towards “valuing” Aboriginal culture – you were probably taught a few myths about Australia’s indigenous people and their history. I have a vivid memory from primary school of crushing up bits of rock and mixing them into water to make Aboriginal “paint,” and thinking to myself how pitiful life must have been back then.

Thankfully, historians have now taken us past these popular prejudices. The history produced by historians is ethnocentric in depending on documents produced by Europeans, but it still offers compelling insights.

The No.1 myth now being dispelled is the “nomadic hunter gatherer myth,” the idea that indigenous Australians went here and there, collecting the odd fruit or nut and hunting game as they went. Certainly, many indigenous groups were mobile, but they were not wandering randomly.

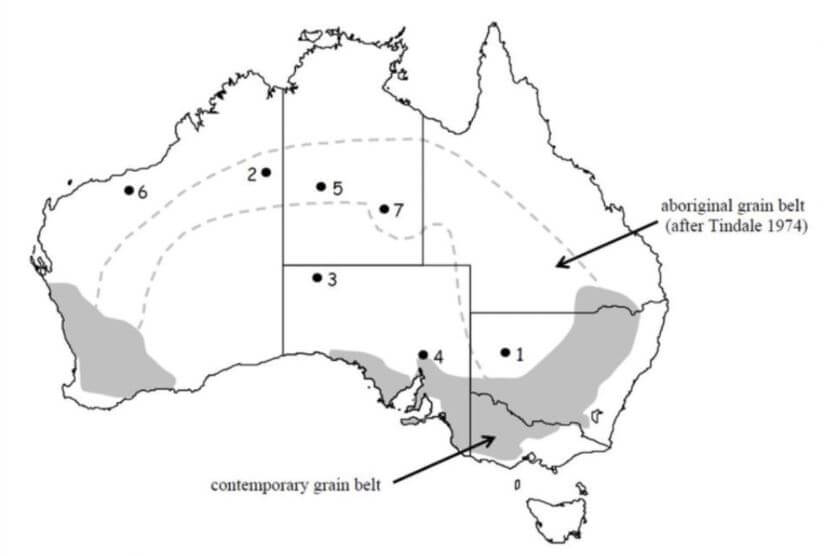

On the contrary, Aboriginal Australians actively managed the landscape. In many areas, this included tilling and cultivation of staple crops, such as the murnong tuber (see feature image) grown in wetter, coastal areas. There were also a number of native grains grown in drier, inland areas, which Australian farmers working in the European tradition today are not able to cultivate.

This area includes archaeological sites with some of the oldest grinding stones found anywhere in the world. As Bruce Pascoe puts it, “Aboriginal domesticates do not require any more moisture than the Australian climate provides, no more fertiliser than our soils already contain and, as they are adapted to Australian pests, they need no pesticides.”

So Australian indigenous history was not some sort of “primitive” struggle for bare survival. In Arnhem Land, for instance, early anthropologists found that adults worked just four hours per day.

Australia’s hard right has had an allergic reaction to the notion of indigenous Australian agriculture, culminating in Peter Dutton’s office attempting to refer Pascoe to the AFP. But Quadrant and The Australian aside, there are moderate and reasonable critiques of Pascoe’s work.

Anthropologist Richard Davis describes Dark Emu as a revisionist account seeking to correct a historical narrative Pascoe perceived as biased against evidence of indigenous agriculture. Similarly, in The Greatest Estate on Earth, historian Bill Gammage says, “People farmed in 1788, but were not farmers.

“These are not the same: one is an activity, the other a lifestyle. An estate may include a farm, but this does not make the estate manager a farmer. In 1788 similarly, people never depended on farming. Mobility was much more important.”

Debates over the historical facts are surely important. Pascoe is right that better knowledge of indigenous agriculture could make Australia more secure in the face of drought and climate change.

Even more important, however, is understanding the interests and prejudices that prevailed in having us taught such a skewed version of Aboriginal history and culture in the first place.

If you enjoyed this article, you can follow Christian on Twitter.