Utah has become the first US state to institute a state-wide book ban in all public schools. Following a law that came into effect at the start of July, a list of thirteen books will now be illegal for Utahn schools to retain in classrooms or libraries. The move has been condemned by activists who say it amounts to censorship and have denounced the legal logic behind it as “anti-democratic”.

While book bans are nothing new in the US, Utah is the first state in which such a ban has been applied state-wide, instead of being limited to school districts. The ban was facilitated by a law called House Bill 29, under which all Utahn public school districts must remove books if they’ve been banned in either three school districts, or two school districts and five charter schools.

Given there are 41 school districts in the state, this threshold has been criticised by groups like PEN America – a nonprofit defending freedom of expression. Director of PEN America’s Freedom to Read programme, Kasey Meehan, said that “allowing just a handful of districts to make decisions for the whole state is anti-democratic.”

A total of thirteen books have been put on the list so far, but groups like PEN assert the list will likely grow as more books meet the threshold. The current list includes Margaret Atwood’s speculative dystopia Oryx and Crake, Judy Blume’s Forever, and Rupi Kaur’s poetry collection, Milk and Honey. Most of Sarah J Maas’ A Court of Thorns and Roses pads out the list, as well as two titles by YA author Ellen Hopkins.

If you haven’t already noticed the pattern, twelve of the thirteen titles are authored by women. The reason they’ve been banned is that these books are considered to contain “pornographic or indecent” material – i.e. depictions of sex or nudity.

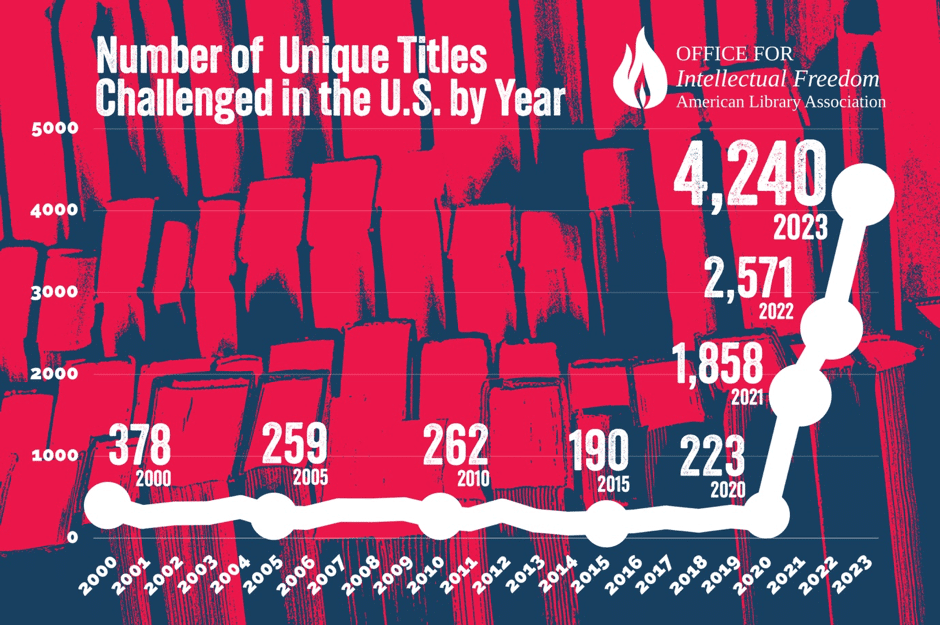

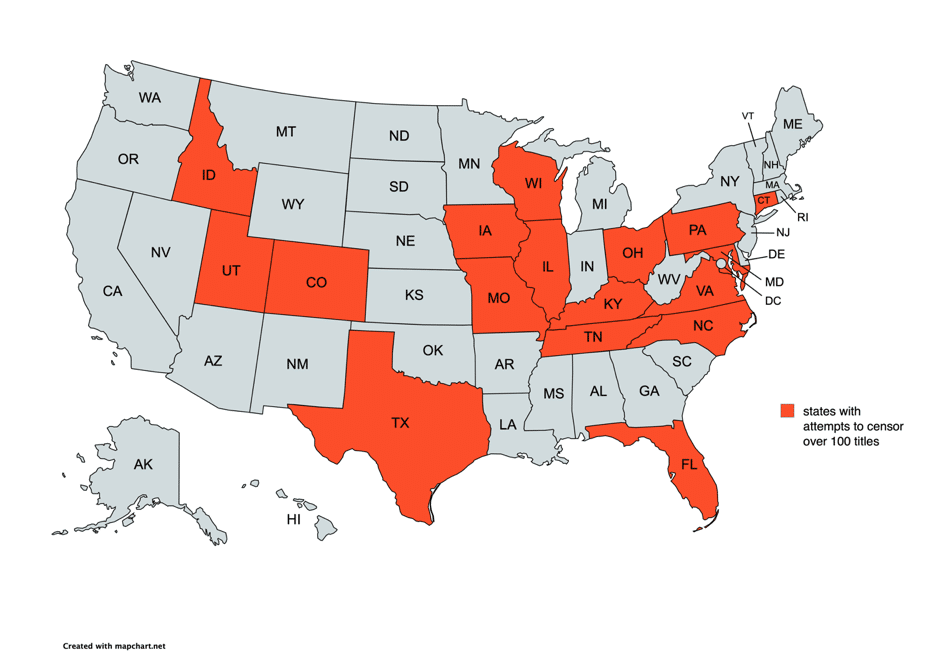

Data from the American Library Association shows that book banning has risen exponentially across the country in the past years. Compared to 2022 numbers, the number of challenges of titles rose 65% in 2023; the highest ever recorded by the ALA. Attempts at censorship of titles were exceptionally high in public libraries, which saw a 92% increase compared to 2022.

The director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, Deborah Caldwell-Stone, called “each demand to ban a book… a demand to deny each person’s constitutionally protected right to choose and read books that raise important issues and lift up the voices of those who are often silenced.”

Her statement reflects the trend whereby books by and about the experiences of people of colour and LGBT+ individuals are disproportionately targeted by book bans. Of 2023’s top ten most-banned books, eight fell into one or both of these categories.

Utahn schools will now have to establish policies for the disposal of these books, which may not be resold or redistributed, or disposed of ‘illegally’. Meehan has criticised these guidelines as “vague”, saying they will “undoubtedly result in dumpsters full of books that could otherwise be enjoyed by readers”.

Reportedly, the Board of Education originally considered language calling for the books to be “destroy[ed]”, with board member Brent Strate stating “I don’t care if it’s shredded, burned, it has to be destroyed one way or another.”

While Meehan acknowledged the final language doesn’t amount to a call for book burning, she says “the effect is the same: a signal that some books are too dangerous”.

Cover photo by Redd F on Unsplash.

Follow Maddie’s journalism on X.

Sign Up To Our Free Newsletter