In the early hours of this morning my maternal grandmother, Eleanor Mary Dawson, born Shiels, died. She was an inspiring woman and it stings badly to lose her.

Eleanor Dawson, Child Psychiatrist

Eleanor was a tenacious and very intelligent woman. It wasn’t until adulthood that I started to understand better how these attributes were so necessary for her to graduate from Sydney University Medical school in 1951, and subsequently succeed as a practising psychiatrist.

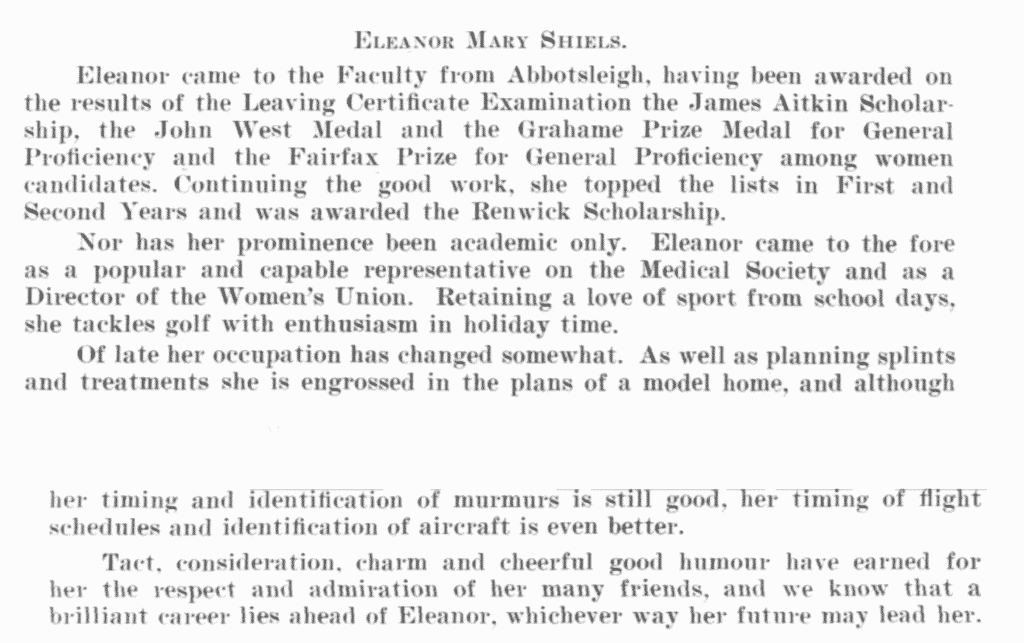

A perusal of the 1950 University Of Sydney Medical School Yearbook shows that Eleanor was one of just a tiny minority of women, and her yearbook entry seems to glide effortlessly from praising her proficiency to referencing her role as a wife (to an aeroplane navigator).

The significance of the comments that “her occupation has changed somewhat” and while her “timing and identification of murmurs is still good, her timing of flight schedules and identification of aircraft is even better,” may be lost on the casual reader. You see, Eleanor, graduating as Shiels, was soon to be a Dawson. She had caused a few ripples by daring to marry my grandfather while still a resident at medical school, only to be quickly informed that married women were certainly not welcomed as residents.

It took me years to hear this story and she never seemed resentful of the extra hurdles she faced as a woman. What she was proud of, in the re-telling, was the initiative she took in convincing the relevant body to continue to facilitate her studies unimpeded. She described to me days spent bussing about the city as a young medical student to personally lobby the committee of (male) practising doctors to whom it fell to decide her fate.

Fighting against a prevailing view that marriage and career didn’t mix (for women), she convinced the committee of a compromise that would allow her to complete her studies unimpeded. So she had tempted fate by marrying as a student; and managed to sufficiently impress the powers that be that losing her would be a loss to the medical profession itself. To me, the reference to her marriage in the yearbook is actually a reference to her hustle.

Eleanor Dawson, Career Woman

As mentioned above, Eleanor’s husband Ted (my grandfather) had trained as a navigator, so with the advent of on-board flight computers, his job became redundant. Around the same time, Eleanor was finding success as a child psychiatrist. Back in those days, there were very few female psychiatrists, and one can only speculate what a difference that may have made for some children, who may have been traumatised by men. She was a successful professional.

While Ted initially started his second career as an accountant, he found it less compelling than the stars and ultimately took on more of running the household while Eleanor worked. Even to this day it is more common for men to focus on work while women look after the home, but taking this approach in the late 1970s was reasonably avant-garde. Her eldest son Jeremy recalls plenty of other lady doctors amongst her friends and that Eleanor’s mother was also a career woman, and no doubt an inspiration to her in that regard.

Eleanor Dawson, Grandmother

I mostly wrote this article because I think it’s inspiring how women of the 1950s overcame so many hurdles to have successful professional careers. We have a long way to go as a society but the contribution from competent, respected, and successful women like Eleanor truly did show society that women can, and should, do these important jobs.

That said, as a grandmother, Eleanor was an influential presence in my life. She could be fiercely interested in my life, and I could have been more gracious about this as a teenager. Looking back, she was always there for me, whether with practical help (including a welcoming home) or to listen and give advice. She and my grandfather were generous with all their grandchildren, but maybe I needed her most. As a child, I felt her sympathy for me strongly, when I faced my own challenges. And as an adult, the list of times she came through for me is long. Every time I ever reached out to her, she was there to take my hand. I can only hope to be such a good grandparent, one day.

One of Eleanor’s quirks was her affinity for the idea that significant life events had coincidentally happened at the same ages to members of her family line. She would reference this in her conversations obliquely, as she researched her family tree back to the Irish potato famine. Some of her research ended up in this blog post from Trevor Mcclaughlin on Earl Grey’s Irish Famine Orphans.

I guess she convinced him to include a poem she wrote, which reflected on events at certain ages in her family. It sends shivers down my spine to read her lines:

“…at twenty-one my eldest grandchild told me of his dream-

a dream of living with his soul-mate in a tree house

and taking babies for picnics in a forest.

with an email chuckle-sign he asked for help-

help to work out how to make his dream come true.”

What she doesn’t say in her poem is that she did it.

She helped me.

So many times, right to the day she died, and beyond.