Since 2020 we have learned that ventilation is one of the best ways to prevent COVID. One study found an 80% reduction in COVID transmission in actively ventilated schoolrooms.

Yet ventilation isn’t only important for COVID prevention. A recent investigation by ARINA and the ABC found seriously high levels of carbon dioxide in many Australian schools.

Australia is one of few developed countries with no mandatory levels for indoor air quality. Australia’s National Construction Code specifies indoor carbon dioxide levels should not surpass 850 ppm.

The Earth’s atmosphere is currently about 420 ppm CO2. Cognitive impairment can be detected starting at about 1,200 ppm.

The joint investigation found absurdly high carbon levels in classrooms, well above these standards. One such classroom reached 3,500 ppm. Another, with a window and a door open, still surpassed 2,000 ppm.

Only the classrooms with active ventilation systems stayed below 800 ppm in this investigation. Such systems are, however, unfortunately rare across much of the country.

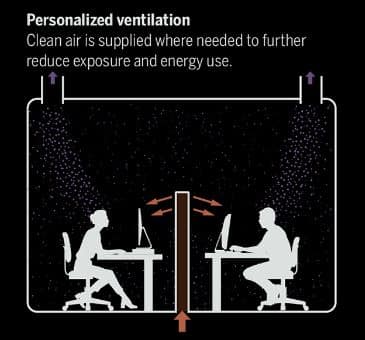

But it doesn’t have to be this way. In the aftermath of the Spanish Flu, the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra Orpheum was built so as to draw air through vents under the seats and out through the building’s roof. Ventilation can be designed based on the use case for a room or building to minimise cross-contamination through the air.

As Professor Lidia Morawska wrote in 2021, while we take lots of steps to prevent food- and water-borne illnesses, we tend to see respiratory contagion as inevitable. It is built into our architecture through lack of ventilation.

COVID has become less of a focus for many thanks to the world-leading take-up rate of vaccines in Australia. But the tragic experience should also remind us that other respiratory diseases – like cold and flu and its regular spread in the autumn and winter months – need not be seen as quite so inevitable as we tend to see it.

Thumbnail image courtesy of @saadchdhry via Unsplash.